space #1 - gallery

space #1 - gallery

space #2 - showcase

space #3 - window

Juan Downey: compartir la alteridad

Nuria Enguita y Nacho París

Sólo si abordamos la tecnología como ecología podemos subsanar la división entre nosotros y nuestras extensiones. Necesitamos poner buenos instrumentos en buenas manos, y no rechazar todos los instrumentos solo porque se han utilizado mal en beneficio de unos pocos.

Radical Software. vol.1, núm. 1. 1970

El discurso estético debe parecer una hipótesis (no necesita pruebas), o convertirse en un símbolo que se sostendrá aún en la ausencia del enunciador. La obra de arte no necesita un descodificador: cada receptor interpreta y recrea.

Juan Downey. Tayari. Jueves 10 de marzo de 1977

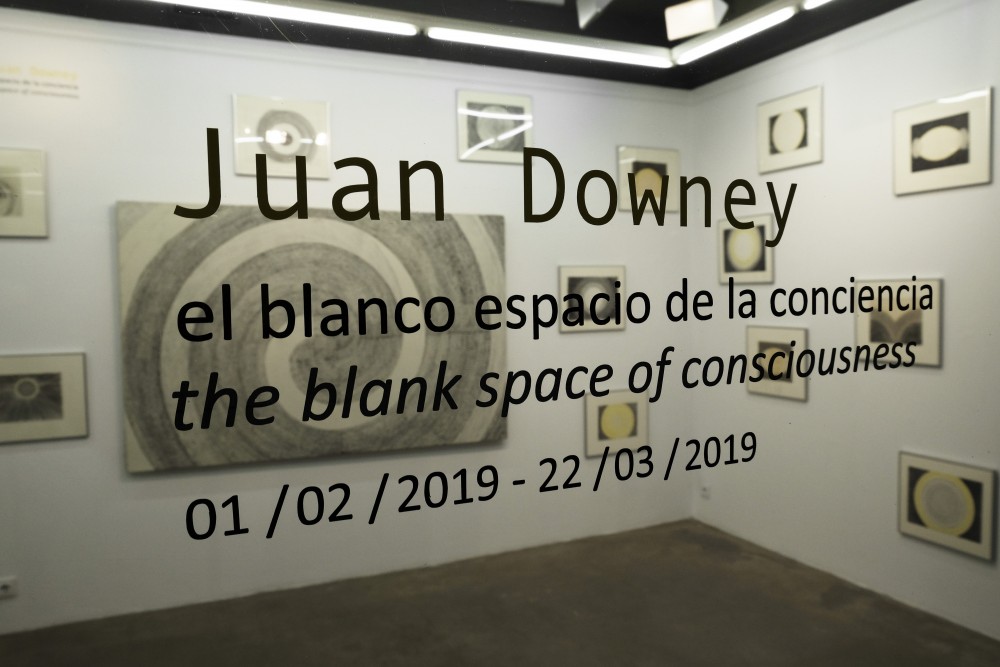

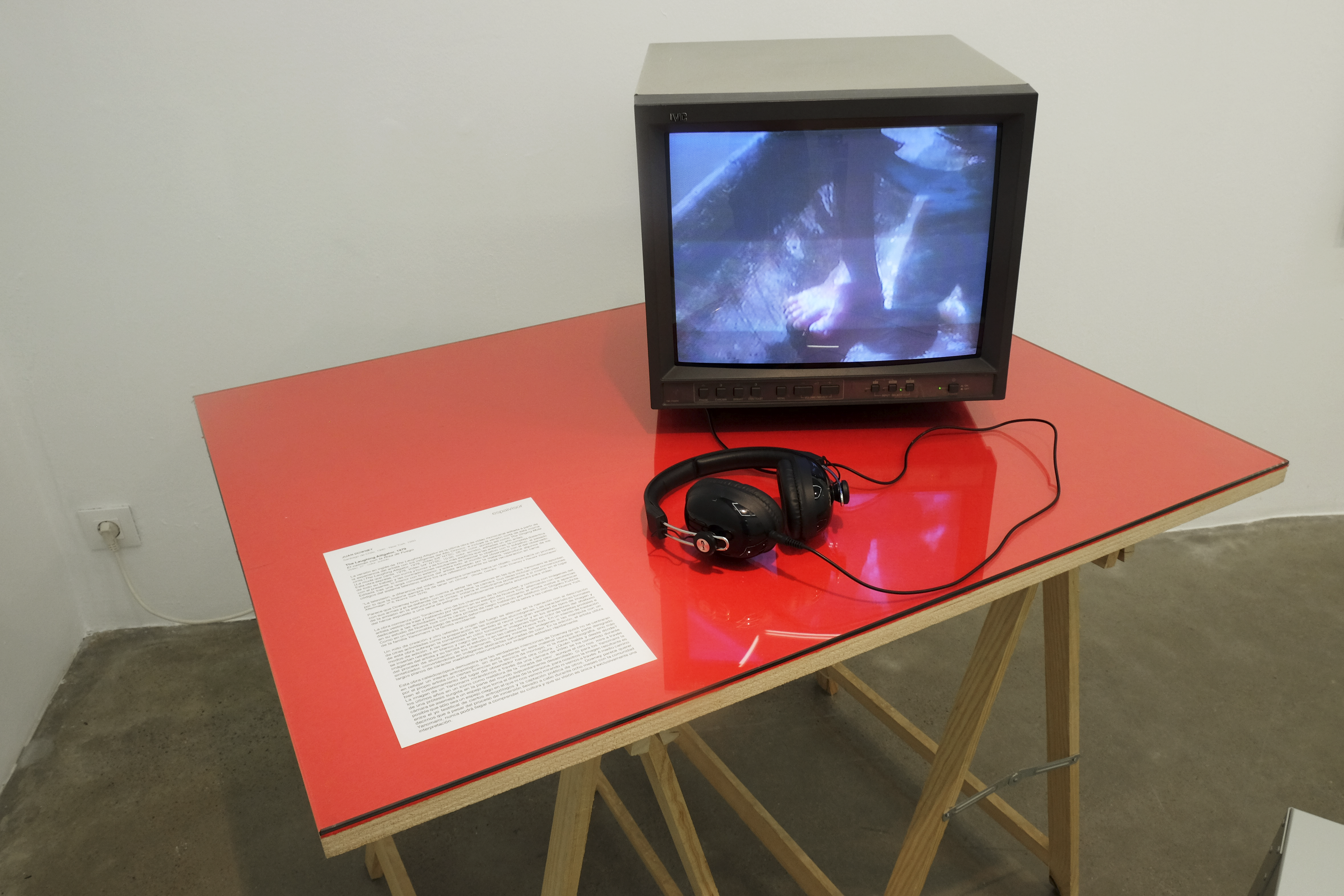

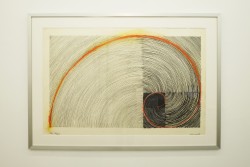

En 1998, hace ya mas de veinte años, el IVAM llevó a cabo la primera retrospectiva europea del trabajo de Juan Downey (Santiago de Chile 1940 - New York 1993). Desde entonces han sido escasas las posibilidades que hemos tenido de volver a contemplar su obra en Europa. La exposición que se lleva a cabo en espaivisor se compone de fotomontajes y dibujos producidos todos entre 1976 y 1978 y de dos videos: The Abandoned Shabono (27 min., 1978) y The Laughing Alligator (28 min., 1977) filmados entre noviembre de 1976 y mayo de 1977, cuando convivió principalmente con las comunidades Yanomami de Bishassi y Tayari, dejando como testimonio más de cuarenta horas de grabación y cientos de fotografías y dibujos. Obras que surgen de la intersección entre sus propias meditaciones y la cosmología indígena, con las que, según sus propias palabras, quiere desprenderse de lo doméstico para entrar en otra química, otra velocidad y otros impulsos que transitan las áreas del cerebro, en el “blanco espacio de la conciencia vacía”.

espaivisor nos propone una mirada sobre un periodo muy concreto de la extensa producción artística de Downey, pero central en su trayectoria y que ilustra claramente uno de sus intereses fundamentales: generar, con el video como recurso, una interacción entre diversas culturas desde una perspectiva holística y antropológica. Voluntad definida ya en las series Video Trans Americas, un proyecto anterior, realizado entre 1973 y 1976, que llevó a cabo en tres viajes desde Nueva York hasta América Central y del Sur, y en el que se propuso establecer un diálogo intercultural, intercambiando información filmada de diversas culturas, reproduciendo una cultura en su propio contexto y en el de otra, editando todas esas interacciones en una sola obra de arte. Además, al mostrar conjuntamente toda la producción de ese periodo, de apariencia y técnica tan dispar, se pone de relieve la capacidad del artista para transitar entre lo sensible y lo conceptual, disolviendo una de las oposiciones más tradicionales en la categorización de las artes; poniendo en conexión sistemas culturales diversos, concepciones y representaciones del mundo y la vida aparentemente antagónicos.

Downey, que fue plenamente consciente de la condición de acto político que tenía su trabajo y del riesgo de apropiación y explotación que poseen el arte y la antropología como sistemas de representación (de ahí su voluntad de convivencia en términos de igualdad con los diversos pueblos que visitó), concibió The Abandoned Shabono y The Laughing Alligator desde una particular suerte de etnografía experimental. Una etnografía utópica, lúdica y crítica, con la voluntad declarada de actuar como “comunicante cultural”, articulando formas de vida y cosmovisiones indígenas, experiencia personal, autorreflexión y tecnología, en un encuentro horizontal de lenguajes, culturas y cuerpos, donde el mirar y ser mirado eran mutuos. Este intercambio igualitario de miradas entre él y los yanomamis pudo llevarlo a cabo a partir de la consideración de las posibilidades especulares del video, es decir, de su condición simultánea de imagen y reflejo que posibilitaba que todos fueran a la vez observadores y observados, sujeto productor de imagen y objeto de la mirada. Downey se plantea los prejuicios éticos y epistemológicos inherentes tanto a la representación visual como a la etnografía, desafiando simultáneamente la supuesta objetividad, autenticidad y el universalismo del paradigma etnográfico y de la visión documental. Y propone una profunda interrogación filosófica sobre nuestra concepción del ser en el mundo y los modos de interpretarlo, formulada desde la crítica a los primitivismos; tanto del que le es propio a la mirada colonial, que cosifica al otro y lo convierte en espécimen (mudo) o icono; como del que lo idealiza en tanto que auténtico y primigenio. La experiencia de Downey en el Amazonas es una aproximación simultánea a los Yanomamis y a sí mismo, es un proceso de diálogo y de autodescubrimiento, de observación y de meditación.

Sin duda el valor de la obra de Juan Downey podríamos situarlo en el hecho de que aborda cuestiones que después serían centrales en el discurso crítico, tales como las políticas de identidad, o la deconstrucción de la objetividad documental, que hoy es básica en la producción de cine y video, y por supuesto en el fértil experimentalismo en el uso artístico de las tecnologías. Pero también, y sobre todo, porque nos avisa de algunos peligros que nos amenazan, tales como: 1) la separación entre el hombre y la naturaleza que, a través de la instrumentalización de las potencias de la tecno-ciencia llevada a cabo por el capitalismo y su noción de progreso, anuncia la destrucción de la vida misma; 2) la mirada distante ejercida sobre “el otro”, germen de la insolidaridad, que en su desafecto y extrañeza imposibilita la comunión con la alteridad, la comprensión de un “nosotros global”; 3) el control, absolutamente vertical, de aquello que podríamos llamar tecnologías para la construcción de la verdad, o sistemas de representación de la realidad (medios de comunicación, centros de enseñanza, instituciones para el pensamiento y la investigación…) que, proponiendo una interpretación única y dominante, estrangula la posibilidad de difundir la diversidad de voces, de miradas, de ideas que nos ofrecerían una visión plural y compleja de la realidad; y 4) el peligro existente en el declive de la imaginación política que ha ido minando el pensamiento utópico hasta el extremo de hacernos incapaces de proponer un futuro esperanzador, haciendo que hoy cualquier futuro posible solo sea imaginado, desde una perspectiva distópica, como una pesadilla.

Si tomamos conciencia de que estas cuatro amenazas están cuidadosa-mente imbricadas por los intereses económicos, el desarrollo tecnológico y de-terminados paradigmas culturales, entonces descubriremos que la extraordinaria vigencia del trabajo de Juan Downey proviene, no solo del notorio lugar que ocupa en la historia del arte contemporáneo en tanto que figura singular en el tránsito del arte objetual al arte de la experiencia, pionero del videoarte, del arte tecnológico e interactivo, y figura contracultural de los años sesenta y setenta–, sino también (o quizá más) de su capacidad para enfrentar semejantes amenazas desde el frágil dominio del arte.

Dado que hemos perdido la capacidad de imaginar la ciencia y la tecnología como un puente entre el hombre y el mundo, como una posibilidad de sinergia y reconciliación, de potenciación de las posibilidades de uno en otro, quizá debiéramos mirar el trabajo de Juan Downey apreciando especialmente ese empeño sistémico en construir un discurso poético y utópico desde una ética, o una filosofía ecológica de la técnica y la ciencia. Un trabajo que propone desmantelar la hegemonía unidireccional de la mirada occidental, renegociar las relaciones de poder entre observador y el observado, y finalmente restituir la relación del hombre y la naturaleza a través de una concepción liberadora de la tecnología.

Juan Downey: Sharing Alterity

Nuria Enguita & Nacho París

Only by treating technology as ecology can we cure the split between ourselves and our extensions. We need to gel good tools into good hands — not reject all tools because they have been misused to benefit only the few.

Radical Software. vol.1, no. 1. 1970

Aesthetic discourse should be like a hypothesis (with no need for proof), or become a symbol that would be sustained even in the absence of an enunciator. The work of art does not need a decoder: each receiver interprets and recreates it.

Juan Downey. Tayari. Thursday 10 March 1977

The first major survey in Europe of the work of Juan Downey (Santiago de Chile 1940 - New York 1993) was held at the IVAM in 1998, just over twenty years ago now, but since then there have been scant opportunities to see his output in Europe. This exhibition at espaivisor comprises a series of photomontages and drawings made between 1976 and 1978 and two videos, The Abandoned Shabono (27 min., 1978) and The Laughing Alligator (28 min., 1977) filmed between November 1976 and May 1977, when he lived among the Yanomami communities of Bishassi and Tayari, a period that gave rise to over forty hours of recordings and hundreds of photographs and drawings. These works came from an intersection between his own meditations and the indigenous cosmology, with which, in his own words, he wanted to get rid of the domestic and engage in another kind of chemistry, another speed and other drives that cut across different areas of the brain, in the “blank space of empty consciousness.”

The show at espaivisor focuses on a highly specific yet absolutely pivotal period within Downey’s extensive output, which clearly illustrates one of his core interests, namely, to prompt interaction between different cultures from a holistic and anthropological perspective, using video as a resource. This enterprise had already been rehearsed in the series Video Trans Americas, a prior project, made between 1973 and 1976, undertaken during three trips from New York to South and Central America in which he proposed establishing an intercultural dialogue, exchanging filmed information on diverse cultures, reproducing a culture in its own context and in the context of the other, and then editing all these interactions in one single artwork. In addition, by exhibiting all the production from this period, so outwardly and technically disparate, in the one place, the viewer can get a better idea of the artist’s capacity to negotiate between the sentient and the conceptual, dissolving one of the most conventional oppositions in the categorisation of the arts; connecting apparently conflicting cultural systems, conceptions and representations of the world and life.

Downey, who was keenly aware of the political agency of his work and of the risk of appropriation and exploitation inherent to art and to anthropology as systems of representation (therein his will to coexist on equal terms with the various peoples he visited), conceived The Abandoned Shabono and The Laughing Alligator from his own personal brand of experimental ethnography. It is a utopian, playful and critical ethnography, with the declared intention to act as a “cultural medium”, articulating indigenous ways of life and worldviews, personal experience, self-reflection and technology, in a horizontal meeting of languages, cultures and bodies, in which looking and being looked at are mutual actions. This equal exchange of gazes between himself and the Yanomamis was enabled by the consideration of the specular potential of video, in other words, the simultaneity of the image and the reflection which meant that everybody could be at once an observer and observed, a subject who produces the image and the object of the gaze. Downey addresses the ethical and epistemological prejudices inherent both to visual representation and to ethnography, simultaneously challenging the purported objectivity, authenticity and universalism of the ethnographic paradigm and the documentary vision. He also proposes a profound philosophical questioning on our conception of being in the world and ways of interpreting it, predicated on a critique of primitivisms; understood in terms of the colonial gaze, which reifies the other and turns it into a (silent) specimen or an icon; and also in terms of what is idealised as authentic and primeval. Downey’s experience in the Amazon is a simultaneous approximation to the Yanomamis and to himself, a process of dialogue and of self-discovery, observation, and meditation.

The unique contribution of Juan Downey’s work unquestionably lies in the fact that he tackles issues which were to become central to critical discourse, for instance, identity politics, or the deconstruction of documentary objectivity, now widely accepted in film or video production, and, of course, in his productive experimentalism in the artistic use of technologies.

But also, and above all else, because he warns us about dangers that loom over us, such as: 1) the separation between man and nature, which, through the instrumentalisation of the potential of techno-science by Capitalism and its idea of progress, adumbrates the destruction of life itself; 2) the gaze over “the other” from one remove, which engenders a lack of solidarity and whose distance and estrangement forecloses any possible communion with alterity or understanding of a “global us”; 3) the absolutely vertical control of what we could call technologies for the construction of truth or systems to represent reality (media, education centres, institutions promoting research and thinking, …), a control based on a single prevailing interpretation that stifles any possibility of diffusing the diversity of voices, gazes and ideas that might afford us a plural and complex vision of reality; and 4) the threat in the impoverishment of the political imagination that has gradually undermined utopian thinking to the extreme of incapacitating our ability to propose a hopeful future. Today it seems that the future can only be imagined, from a dystopian perspective, as a nightmare.

If we are aware of how these four threats are meticulously interwoven by vested economic interests, technological development, and particular cultural paradigms, then we will realise that the extraordinary currency of Juan Downey's practice is owing not just to the place he has staked out in the history of contemporary art, inasmuch as a lynchpin in the transition from object-based to experience-based art, a pioneer of video art, technological and interactive art, and as a counterculture figure from the sixties and seventies, but also (or perhaps chiefly) for his ability to confront these threats from the fragile terrain of art.

Given that we have lost the ability to imagine science and technology as a bridge between man and the world, as a possibility for synergy and reconciliation, of enhancing the possibilities of one in the other, perhaps we should look at Juan Downey’s work with a particular appreciation for his systemic endeavour to build a poetic and utopian discourse from an environmental ethics or philosophy of technology and science. A practice that proposes dismantling the unidirectional hegemony of the Western gaze, renegotiating the power relationships between observer and observed, and ultimately restoring man’s relationship with nature by means of a liberating conception of technology.

espacio #2 - showcase

LOUIS-CYPRIEN RIALS

Geological Horizon

In collaboration with Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris

Louis-Cyprien Rials travels, films and photographs as a solitary citizen. From either ordinary or sacred lands, his productions bring back another story than the one manufactured and conveyed by television news. It is a story full of ghosts, deserts, wars and sceneries that men and women now only inhabit through their vestiges and stigmata which are shadows of themselves. Motorcycling through Odessa in order to discover the abandoned zones of Chernobyl, hitchhiking through Iraq with no money: Louis-Cyprien Rials is often just about to leave, on his way to the representations of the sacred in these territories where the questions of religions, customs and rites are confronted with the political and economic stakes in connection with the natural resources or the geographical situation. He has for example, crossed the former Yugoslavia, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Iraq, Georgia, Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh and Crimea.

While defying himself as both an artist and an activist, he nevertheless distinguishes his art from the situations that drive him to make it. Other products of his travels include documents, a Web blog diary and open use documentary photos “to give these situations a face so that people can understand”. The transmission of knowledge is important to him. He has been doing documentary work for a decade, learning from his father, an expert in international law and geopolitics, and the family library. ln 2013, before the emergence of Daesh, he was set to make a two part documentary called Holy Wars, based on eyewitness accounts The project was abandoned for lack of funding “Everyone has their own opinion”, he explains. “What I want to offer people is a terrain of comprehension. I don’t try to make them adopt my point of view.” Rials also studies on a mental and miniscule scale the breathtaking landscapes that nature creates and randomly locks into various rocks and which can be revealed through polishing. He photographs them and prints them onto large formats (the series Pierres [Stones] which started in 2007). It is, for this humanist of a new kind, another way of talking about the world that shelters us. Some of the voyages that move him don’t require travel. For the last ten years this connoisseur has collected “image stones” from all over the world. He photographs them, blows them up and colorizes the negatives to make prints that look strangely familiar. “l’ve come to understand that at certain points art history was profoundly marked by designs found in stones. You can see that in many schools of art from Japanese prints to Cubism, but the same motifs are also visible in every possible landscape, whether cliffs, seas or deserts. My work is a reflection on solitude, voyages made without actually traveling, dreams and humanity.”

This artist is on a quest for humanity. He refers to pareidolia, the tendency of the mind to identify clear patterns or images where none exists. “It’s as if Earth created a kind of photo collection on rocks, something that only human beings could perceive. I feel that recognizing something in something else, for example a landscape on the surface of a rock, is a sign of intelligence and proof of our humanity.” Rials plunges into the depths of a stone just as he does into the depths of history. From that he draws the strength of his work and his desire to share his knowledge and discoveries.

Léo Marin

Publication