space #1 - gallery

space #1 - gallery

space #2 - showcase

space #3 - window

MLADEN STILINOVIĆ

Igor Zabel

A Short Walk Trough Mladen Stilinović's Four Rooms

Room

A room, in the case of Mladen Stilinović, is not just an exhibition space. It is a form of organization and presentation of the material. It is, of course, connected to the tradition of conceptual and post-conceptual art and to those tendencies in art that have searched not only for new forms of artworks, but also for new forms of creating and presenting art and for new relations with the audience. Stilinović doesn't take the gallery space for granted, and this is perhaps connected to his experiences with the Group of Six Artists, a group of avant-garde artists active in Zagreb since 1975. The group invented a particular term that describes the way the artists presented their works. They have called these events (that took place on streets, in parks, on swimming-pools etc.) “exhibitions-actions”. The term indicates a particular way of thinking of production, presentation and reception of the works of art. At an “exhibition-action”, all three aspects were connected in a single interactive and collaborative creative process.

The room implies a slightly different structure. It is probably less connected to a process than an “exhibition-action” and more to reflection, interpretation and re-interpretation. A room is defined by a certain common theme. The theme can be a medium, a motif, a subject, etc. As he compiles and arranges such rooms, the artist builds a sort of taxonomy of his own art and thus defines the basic dictionary for understanding it. In spite of the broad variety of approaches, media and subjects in his art, we can also find in it a particular systematic approach, visible both in his works and in the way he re-arranges in re-interprets his own pieces. A dictionary would be indeed a very appropriate way of presenting his work (after all, Stilinović has used dictionary several times); of course, such dictionary would necessarily be a highly complex network of cross-references.

A room is a space where works of art of different types and from different periods can be arranged together in a single pattern. The artist does not arrange them in the usual linear sequence. Rather, he covers walls with his works, constructing patterns and building new connections. Since Stilinović’s work is closely related to literature and visual poetry, we could, perhaps, find a relation to the way Mallarmé dispersed the usual linear structure of the poetical text in his book One Toss of the Dice, producing new meanings with the spatial structure of the text and with the position and size of the words, and incorporating empty space into the text. In a similar way, Stilinović’s works – that are, of course individual pieces – gain new meanings from their location and relations to other pieces, developing and weaving complex micro-relations that eventually produce the main theme of the room.

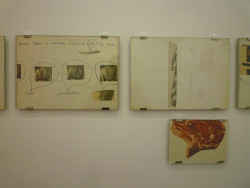

Finally, the room indicates a position that is different from the usual position of a museum or gallery visitor. Stilinović often organizes small exhibitions in his own apartment, and the way the works are presented in a gallery space can be directly related to the way they are presented in his study. This is a reason why the relation of the visitors to the exhibited works can be more intimate and immediate. Indeed, such relation is important, since the works are usually not what we call “museum pieces”. Rather, they are mostly small-sized works that often demonstrate how a thought or idea has been developed, and not monumental statements. This, again, is closely connected to Stilinović’s artistic strategies. His artistic work is actually a tightly knit network of micro-strategies, of very different ideas and approaches that, nevertheless, form clearly recognizable patterns and taxonomies.

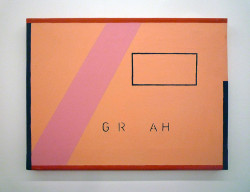

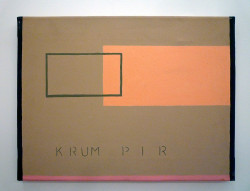

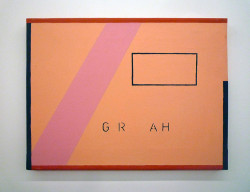

The Red (and Pink) Room

Soon after the death of Pope John Paul II, a Slovenian newspaper (that could be described as both “yellow” and “black”) published a few articles that attacked the journalists of the TV Slovenia. They accused them of disrespectable behavior during the Pope’s last days. And what exactly was the disrespectable behavior? The host of the main evening news wore a red tie, and the journalist reporting from Rome a red dress. Not only they were disrespectful towards the Pope and the mourning believers, claimed the newspaper, but they also defiantly declared that their disrespect is based on their political stance. The red tie of the TV journalist was, in the eyes of the newspaper’s editor, a red flag that declared that the television was still a “red fortress.” The true content of this attack is, of course, quite obvious and is directly connected to the attempts of the right-wing government to gain full control over the public television. What is, however, interesting for us here is its “exterior” form. The red pieces of garments worn by the journalists of the TV Slovenia were considered a disrespectful political provocation. At the very same time, Vatican was literally crowded by people in red garments. But in this case, red was not considered to be either disrespectful or a sign that Vatican was, in fact, a “red fortress.”

The case of the red tie, absurd as it is, demonstrates at least two important issues. First, the use of color is not innocent and unburdened by possible meanings. Such meanings are not even necessarily meant by the person that used such color. (Personally, I do not believe that even the newspaper’s editor actually thought that the correspondent reporting from Rome chose her fashionable red dress – quite similar to the dress in which the American State Secretary appeared on some of her recent official visits – in order to demonstrate her leftist political preferences.) And second, such meanings are not fixed and stable, they can change according to the situation in which they appear, they can actually be constructed according to the context. Slavoj Žižek once demonstrated the way ideology operates in the every-day life by describing different concepts that achieve a tangible form in different types of toilets. His point was that it was enough for one to sit on the toilet to find oneself deep in ideology. On the other hand, one cannot avoid ideology since one has to use a certain type of toilet, and even a decision of not using it would be an ideological form. In a similar sense, wearing a tie of particular color (or not wearing a tie at all) places one in a fluid network of political and ideological meanings.

Colors are very important for Stilinović’s art. One could attempt to present a system of colors he uses. White, for example, indicates emptiness and nothingness, black is the color of death, red is the color of ideology and political power, pink could perhaps be connected to consumerism. Furthermore, the meaning of colors in Stilinović’s works is directly connected to the use of colors in modernist and avant-garde traditions, and particularly in Malevich’s Suprematism. It would be, however, wrong to assume that Stilinović has been developing a kind of firm defined symbolic or even esoteric system of colors. Quite the opposite, colors seem to be for him always ambiguous, indicating certain contents, but not clearly signifying them, speaking with their material immediacy and appeal, and yet unable to get completely rid of their possible meanings.

Red color has a particular role in Stilinović’s work. This importance is not connected only to its importance in the public life in the socialist Yugoslavia in the 1970s and 1980s, but it its extreme importance for the global history and culture in the last century or century and a half. Red has become extremely burdened by meanings. As we saw, merely wearing a red dress can become a source of complex political and ideological hermeneutics. On the other hand, such meanings are far from being simple and clear. The Russian artist Valery Kosolapov, to name just one example, used in his work Lenin – It’s the Real Thing (1982) red color both as the color of the socialist revolution and of the registered trade mark of Coca Cola, thus dialectically bringing together the two opposing political and economic systems and disclosing their parallelisms. And even if we identify it with the communist revolution, the red color again implies very different contents, from the protest against a non-egalitarian and exploitative society to the idea of totalitarian and repressive communist societies.

In a short text Stilinović describes very precisely and concisely his “use” (as he says) of the red (and pink) color. He emphasizes exactly the plurality of meanings that are necessarily connected to it. His strategy is to exaggerate this plurality, so that any attempt of meaningful interpretation would eventually lead into an absurd situation. In such a way he tries to deconstruct the meanings and, as he says, “de-symbolize” the color that can eventually be understood just as color. On the other hand, however, it is simply impossible to forget different symbolic networks that determine it. Therefore, says the artist, “one reads these works both as symbols and as de-symbols.”

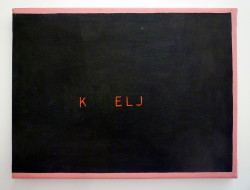

The Room of Words, Slogans, and Proverbs

Words have always been a central part of Stilinović’s art. His works have seldom been “purely” visual. Even pieces that do not actually include written words are often connected to the structure of the language; either their own structure is based on linguistic structures or they are visual representation of such structures (e.g. the works that are based on the play with words). However, the visual side of such works is not unimportant, either. Stilinović’s works point at the fact that the way a text is physically represented (and this includes such details as the type of writing, the material, on which the text is written, the colors used in writing, the context in which the written words appear, etc.) strongly affects its meaning.

This is, perhaps, particularly visible with the works where the text refers to the work itself. For the work of the Group of Six, the aspect of self-reflection in art has always been essential. They have used in their work approaches that come from so different sources as, for example, the so-called “fundamental” or “primary” abstract art or the concrete and visual poetry; the common aspect of such diverse practices is, however, the self-referential and self-descriptive character of the work. It is, however, typical for Stilinović that he often used such approaches in an ironic and playful way, so that the results can be humorous and even absurd. One of his works, for example, consists of a hand-written statement that declares, “I have been working on this work since 11 June 1976.” The content of this piece (or, better, this work) is, quite in accordance with the fundamental demands of the “primary” art, a presentation (even a direct description) of its own conditions and the process of its production. And yet, this approach is here turned into absurd. A similar, even more exaggerated effect of absurdity can be found in Stilinović’s handwritten booklet called I Have No Time; the pages of the booklet are completely filled with endless repetitions of the sentence “I have no time.” Both works clearly show the complexity of Stilinović’s approach, hidden behind what at first seems simply a witty idea. They deal with the issues of work and time, of “having” and “using” time, of empty time, etc.

The self-referential character of Stilinović’s work, however, cannot be limited to those works that describe the actual material and temporal conditions and processes of their own making. It is no coincidence that Stilinović uses the word “works” rather than, for example, “pieces”. A “piece” is an autonomous entity, a “work”, on the other hand, is an element in the social network of work and production. For “primary” and “fundamental” art, the production of a work consists of its material characteristics and the actual, physical process of making. Stilinović, however, shows that this process of making is not self-sufficient. Rather, it is included in the network of the social exchange. A “work” is produced in order to be consumed; moreover, it is produced to be sold. One of Stilinović’s works announces that in a rather direct way: “I sell works, I buy hard currency.”

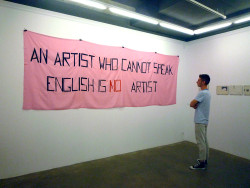

We should understand this sentence not only as a metaphorical description of the position of the artistic production, but also as a direct and simple description of the situation it refers to. It is a good example of Stilinović’s statements and slogans that seem to be witty paradoxes or exaggerations but should be, nevertheless, often taken literally. The best known of these statements are, perhaps, “An artist who cannot speak English is no artist,” and “Work is illness,” a fake quotation from Karl Marx. At first, the statement, “An artist who cannot speak English is no artist” seems absurd – why should knowledge of English be a condition of being an artist? And yet, we should take the statement quite seriously. One cannot simply decide that he or she is an artist. One can only be considered an artist if one is accepted by the system of art. Not every practice that could be, in one way or another, described as art, is acknowledged by the system of contemporary art. Therefore, to be an artist, one should follow the demands of the system and accept the practices that it approves; he or she has to speak the language accepted by the system. The system of contemporary art is declaratively international or global. Artists and curators often do not want to be described as representative of a particular state or nation and prefer to be described as “international.” English is, so it seems, consensually accepted as the language of this global system. We often see how artists use English in their works not only to be able to communicate internationally, but also to emphasize that they belong to the world of contemporary art. And yet, the generally accepted use of English as the dominant language of the system indicates that there exist more or less hidden inequalities, relations of dominance and subordination, of centers and peripheral areas. Briefly, to be acknowledged as an artist one has to speak the language of contemporary art, that is English, and thus tacitly accept the relations of power and dominance that govern it.

Stilinović’s statements often deliberately imitate the form of political slogans. (Let us just think of his declaration, “An attack on my art is an attack on socialism and progress!”) His interest in this textual (literary?) form is certainly connected to the experience of such slogans and other forms of political propaganda in the socialist society (we should mention the series of photographs of such slogans as they appeared in display windows and other public places). In Yugoslavia, the 1970s were a period of a strong ideological pressure that was visibly displayed in ideological propaganda. It is thus no coincidence that Stilinović and several other members of the Group of Six Artists referred to this form in their work and adapted it to their practice. For them, it was interesting not only for its immanent contradictions and absurdities that they often revealed in their works, but also as an example of a very close connection of language and power. A political slogan can be considered a rudimentary poetical form and is, at the same time, a very direct mechanism of ideological and political power. It comes as no surprise that Stilinović and other members of the Group of Six Artists, who have always been deeply interested in the relations of the poetical and the political, found it so interesting.

One could perhaps say that Stilinović’s textual works address in the most explicit way a tightly connected group of issues that are essential for his art in general. These issues include work, time, money (and poverty), food (and hunger), and power. We could say that he shows how political power uses different ideological mechanisms (from political slogans to media representations and moral norms) to construct and maintain social relations in which it could be sustained and reproduced. Such relations are, of course, relations of inequality and exploitation. Power can reproduce and increase itself only through keeping majority of people in a relative poverty, through exploitation of their work, and by persuading them that such social relations are natural. The artist, however, is not interested primarily in developing a general theory on power and work. Such general ideas are, rather, a background of a sort, while he actually works on the micro-level, building a network of references and their combination and constructing a multi-layered reflection on the issues of dominance, production and reproduction and their relations.

The forms of slogans, proverbs and sayings are particularly interesting in this context. They are directly involved in the way power reproduces itself through organizing social relations. They are short formulations of such relations in the form of “naturally valid” ethical norms and moral aims (e.g., “Who does not work shall not eat”). On the other hand, they are often clear and pointed descriptions of the nature of such social relations (e.g., “A poor man has no friends”).

The Newspaper Room

They say that nothing is older (and more old-fashioned) than yesterday’s newspaper. And yet Stilinović’s approach to the newspapers indicates that they have a more general and more permanent value. The way he uses them indicates that he discovers in them particular structures and mechanisms that are firm and permanent in spite of the newspapers’ highly transient value.

A newspaper is some kind of a map of time. A map is always reductive and schematic, and it no less constructs than represents its territory. In a similar way, newspapers function as mechanisms of selection and combination that, in endless repetition, reflect and for the same token construct time, i.e. the historical moment. To be able to do their functions they need to have certain permanent structures, which select and organize the endless flow of different information, present them as news and thus continue to construct the map of time. Such structures are primarily formal. They are not contents, but a way of organizing such contents. They are perhaps most visible in different permanent graphic forms, in newspaper’s layout etc., as well as in the system of editing that makes possible for us to learn about the news quickly and effectively. Less obvious, but not less important are typical textual forms used by the journalists in their texts. We often feel how empty actually such forms are, but it is exactly this formal aspect that is effective and functional. Images, too, show a similar tendency to schematization. Photographs representing congresses and sessions have a certain general quality. They are almost interchangeable. The same is true even of portrait photographs. Individual features often disappear in favor of a generalized image of a representative of power (who can be a communist leader, a western politician or a director of a big company).

Stilinović seems to be particularly interested in such schematic forms – i.e., in the forms that construct historical time and its relations. Often, he even emphasizes their formal nature by taking them out of their original context and presenting them as autonomous structures. Another approach that he often uses is re-contextualization. This doesn’t mean only that he moves fragments of newspapers in new contexts; often, he determines such new context by writing short textual comments or adding drawings or other elements. There is a series where he combined small fragments from newspapers with fragments of small every-day conversations. In such combination, both seemingly unimportant types of fragments gained a particular weight. They now seem to be loaded with particular, albeit unclear meaning and emotional importance. In a similar work, Stilinović took schematic political statements from article titles and added to them obscene comments, such as people often have as they read newspapers.

Such re-contextualization can also be achieved by crossing two different series of works, i.e. two different taxonomies. An example of such crossing of systems is a series of works that combine political slogans with article titles that refer to workers’ strikes. Simply by systematically opposing two schematic textual forms from two different times, i.e. slogans and references to workers’ protests, Stilinović develops a complex discourse about actual social tensions and conflicts. The slogans, of course, serve as a tool to discipline the society, and especially the working process; they also function as a screen that hides the actual relations of power, dominance and exploitation that govern the working process and society in general. On the other hand, workers’ strikes clearly disclose the unbearable conditions of working and living, and thus the exploitative system of social inequality.

What is also interesting for Stilinović’s approach to newspapers is the way he finds little details in them that – taken out of their original context and isolated or placed in a new, unusual context – speak with incredible richness, complexity or even poetic power. This, however, is possible because of a particular way of reading. Only in such a way can, for example, results of sport matches or statistics be transformed into a poetic reflection on numbers and zero (nothingness).

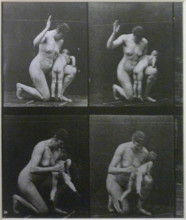

The Photography Room

The photography room is different from the other rooms, as it is not based on any particular subject or issue, but on a particular medium. If we could say that the rooms indicate a particular taxonomy that is a basis of Stilinović’s art, then we could also say that they no less show, how closely and essentially are different issues connected. We could show numerous examples that could make part of two, maybe even three or four rooms. The photography room that is not based on any particular subject makes even more obvious that different issues and subjects actually exist as a tightly knit, interconnected network. Each of them is related to and determined by others.

It is, nevertheless, no coincidence that photography, of all media, selected to be represented in a room of its own. In Stilinović’s work, as well as in the work of other artists of the Group of Six Artists, photography has had a particular position. Stilinović and other artists of the group not only used photography in their work, but also systematically and critically analyzed its structure, role and position. (This critical and deconstructive tendency reached one of its most extreme result in the project by Željko Jerman, who wrote with photo chemicals on photographic paper, “Drop dead, photography!”)

Photography as a medium, on the other hand, has been deeply transformed in the context of the conceptual and post-conceptual currents in art, to which Stilinović’s work is, of course, closely related. It is well known that conceptual artists have renounced the idea of the photographic image as an aesthetic, perfectly executed object and replaced the concern for composition, strong subject and skillful execution with simple, unsophisticated shot that simply registered certain situations, functioning, as it has been said, as a “copying machine”. (It should be, perhaps, noted that conceptual art, in spite of its aspirations, actually did not cancel the aesthetic dimension of photography, but defined new aesthetic criteria for it, not based on values that have traditionally distinguished a well done photographic print.)

We could say that Stilinović uses photography in a number of ways. It can, for example, serve as documentation of ephemeral actions or projects that were otherwise inaccessible to broader public. On the other hand, photography has the ability to register a certain situation and thus, merely by framing and recording it, transform it into artistic context.

It can be used as a tool for research, documentation and classification of reality. This is, perhaps, particularly important for Stilinović’s work. Photography is ideal for the long-term, systematic work of recording and analytically categorizing details of every-day reality. He has been working on several such series. One of them, for example, presents hairdressers’ shop signs. (Two further series represent mechanics’ shop signs and signboards advertising restaurants with barbecue.) The series represents a collection of details of the every-day reality that we often overlook. And yet, thanks to Stilinović’s systematic approach, they not only often prove to be interesting by themselves, but they represent a cultural segment that offers a particular insight into the cultural and social history. One could say that fundamental historical and social structures function through the most marginal and seemingly irrelevant aspects of the every-day life. It is exactly this crossing of the every-day reality and socio-historical structures that is revealed in Stilinović’s series. The visual style of the boards, the type of the letters, the quality of execution, the look of the haircuts etc. construct a really panoramic view of ideas and ideals and their transformations.

In another series, the artist registered elements of ideological propaganda in the public space that used to be an unavoidable part of the every-day life in the socialist society, especially at the time of public holidays. Stilinović systematically documented flags and slogans decorating the streets and more slogans, communist symbols and Tito’s portraits in the display windows of shops and offices. The series has several layers. For example, it clearly shows one of the ways in which a particular type of ideology functioned in the society, how it entered the public space and every-day life. It also shows how schematic actually such slogans and symbols were, and how could they be effective in spite of their schematic, purely formal nature. They indicate one of the essential paradoxes of the way socialist societies functioned. Nobody, including the ruling elites, seemed to actually believe in slogans and rituals that governed the life of such societies; they considered them to be pure forms without any actual meaningful content. However, this was enough for the social order to be able to function as usual. It was not necessary that people believed in rituals, it was enough that they formally complied with them.

On the other hand, Stilinović not only uses photography, he is also interested in its properties and structure. For example, he demonstrates that photography can be an excellent example to study principles of and possibilities of representation; furthermore, he is interested in the structure and nature of its medium, in the wide range of its attributes, from the illusion and reality effects it produces and the symbolic structures it incorporates to its material basis. One should also notice his interest in relation of photography to poetic, or, more generally, linguistic structures.

Re-Thinking the Past, Re-Discovering the Present

Many of Stilinović’s works that are included in such rooms go back to the 1970s and 1980s. That means that they were produced in a very different political, social and cultural context. Many things that used to be taken for granted are not common anymore. These works, therefore, often do not speak to us in the same way as they used to 20 or 30 years ago. This is something we should take into account, since these works are so directly related to social and political issues and circumstances. And yet, they are certainly not mere documents about a past society. If they would only show us interesting details from past decades they would be simply a source of information, or perhaps a source of nostalgia. Their actual subject, however, are patterns of power and dominance, the ways meanings are constructed and the self-evident is determined. They also speak about art’s own relation to power, its possibilities and impotence, its distance towards the structures of dominance and its collaboration with them.

Such patterns are no less functional in the new context of contemporary society as they used to be in their original context. The past forms and structures of power, as they are presented and critically reflected in Stilinović’s works, somehow hold a mirror to the present ones.

Stilinović’s art, however, is not sociology. It is primarily art, but art that is aware of its own conditions and determinants. The artist doesn’t close his eyes from the reality around him – from his own reality. And it is by responding to this reality, to its multiple contradictions and dilemmas, that he is able to recover the poetical, the beautiful, even the sublime.

(2005)

Branka Stipančić

AUCTION OF RED

A look at the 70s

I was free from the court, but I was not free from a lot of other things. Mladen Stilinović.

“Life means not going to court,” a quote from Piero Aretino, famed Renaissance 16th century writer that Mladen Stilinović used in one of his photographic works (1978), could be taken as the artist’s life motto: “not going to any kind of authority, neither political nor artistic, and avoiding it”.(1) The quote always pleased him a lot; he understood court rather widely, first of all dropping out of high school, and then from a great many social obligations that fell on him one after another. He had no wish for regular schooling, and he came by everything he needed himself or with the help of family and friends. He was interested in poetry, and read it from Villon to Khlebnikov, read literature very seriously, was interested in film and so went to the cinema... He was interested in art, and hitch-hiked around Europe, visiting museums and galleries, studying old art and new. He had no expectations that the Film Academy or the Art Academy would help him much in his endeavours. As a sixteen-year-old he listened to John Cage, who in 1963 appeared at the Music Biennale Zagreb, and he saw the dance performance of Martha Graham; he followed American underground films at the Zagreb Genre Film Festival (1970). He was stimulated by numerous events and theoretical writings that arrived in Yugoslavia in translations, which were published in books and journals in the whole of the Yugoslavia of that time. (2)

In the 1960s, Zagreb was an open city. Within the hard-line communist system, culture was an oasis, and through it, Yugoslavia opened up its borders to both East and West. It is well known that the Yugoslavia of the time belonged neither to the Eastern bloc countries nor to the Western democracies. Tito stood for the third way, non-alignment. The standard of living was considerably better than in other communist countries and, perhaps most important of all, there was freedom to travel. To show its distance from the policies of the USSR (which it had broken with after the Cominform Resolution of 1948) Yugoslavia gave tepid support to Modernism, and at major cultural events such as the Music Biennale, New Tendencies, Genre Film Festival (all in Zagreb from the early sixties) artists from East and West were invited, a rare phenomenon in the time of the Cold War. Theoretically, the social and political system of socialist Yugoslavia was based on decisions of the peoples, the working people and citizens, while in practice there was a strict political system with the dictatorship of a single party that made all the important decisions. The economic system known as self-management worked poorly and was in reality totally directed by the state.

The art scene in Zagreb, capital city of the Republic of Croatia, differed from others in Yugoslavia in the much stronger continuity of the historical avant-gardes, visible primarily in the post-war Geometrical Abstraction of the group called Exat 51 and in the neo-Constructivism of the New Tendencies. In the Gallery of Contemporary Art it was possible to follow in continuity the important exhibitions of the historical avant-gardes and of contemporary art, Yugoslav and international, including conceptual art in the seventies.

At the beginning, like many young people, Stilinović wrote poetry, and published some of it in the literary journal Republika. But since his interests were more in the direction of film, with his friends in 1969 he founded the group Pan 69, which was a student cinema club. In order to get hold of film stock and the equipment necessary for making films, this was the only way at that time. Some of the first films were shown at amateur film festivals, but they were fairly different from the production that could be seen there, and so he was invited to places more adapted to his idiom, where the focus was on contemporary visual art. One such place was the Student Cultural Centre in Belgrade that in the 1970s organised an international contemporary art event called April Meetings, which every year in that month brought together significant artists and theorists including Marina Abramović, Neša Paripović, Raša Todosijević and international guests like Joseph Beuys, the Art and Language Group, Germano Celant. Projects were produced there, and one-day exhibitions and performances went on, with music, film and later video screenings, there were lively talks, friendships were made and future cultural projects initiated. These were outstanding encounters indeed, rippling with energy, stimulating for artists and audiences alike, like few in the Europe of that time.

It was at the 4th April Meeting (1975) that Stilinović and photographer Željko Jerman, urged on by such exciting events, agreed on a joint exhibition at the open air. After they returned to Zagreb, they were approached by Vlado Martek, a literature and philosophy student, Boris Demur, then a student of painting, Mladen’s younger brother, Sven Stilinović, and his friend from the Applied Arts School Fedor Vučemilović; the very next month they held their first exhibition – action at the bathing sheds on the Sava. This was not, for Mladen, the first collective with which he undertook joint actions. In 1970, with Pan 69, he had performed in Zagreb, as part of the Student Theatres Festival, his first happening – May and Other Rituals – a political statement in hippy style, forcibly broken up (3) and then with the group FAVIT he performed multimedia events at the April Meetings in 1973 and 1974 and also at festivals in Zagreb and Pula. (4)

The exhibitions - actions of the Group of Six Artists in Zagreb took place under the aegis of the Centre for Film, Photography and Television (known as Cefft) – one of the departments of the Gallery of Contemporary Art, fostered by its curator, then less well known as an artist, Dr Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos, who had to seek permission from the authorities for them to perform on the street. Any kind of private initiative, even just singing or the selling of knickknacks, was not permitted. The impatient artists were unable to wait for calls from the gallery. They said they wanted to show their works at once, as soon as they were created, that they did not want to hide them away, and wanted to be present themselves at their exhibitions, to emphasise the “unity of work and artist”. They showed at various spots in Zagreb: in the old centre of the Upper Town, the new estate called Sopot, on the main city square; in Venice, at the beach in Mošćenička Draga, in Belgrade and elsewhere, spontaneously, as a loose association of artists that put its ideas into practice by appropriating on its own behalf a new type of exhibition context. They spread their works out on the grass, on the road, projected slides and films on the walls of houses. Their works were often destructive of aesthetic and ethical standards, and their actions tended to disturb the public. The creative territory of the artist was broad and widened every day. They were not the first in this country to have chosen alternative places and means of presentation. Before them came the activities of Gorgona (5), the environments and installations of the generation of young artists gathered around the Student Centre Gallery and the exhibition Possibilities for 71 of the Gallery of Contemporary Art, the work of Josip Stošić, Tomislav Gotovac, Goran Trbuljak, Braco Dimitrijević, Sanja Iveković and Dalibor Martinis. Many of the works and actions of artists and groups in these years signalled changes that in their diversity expressed lack of trust in the institutions of culture, Modernist art, particularly its visual self-sufficiency, and each of them, in their own way, carried on the fight. Looked at in retrospect, everything was ready for changes.

At the time of the first exhibition-action of the Group of Six, Stilinović was making collages, artist books, photographs and films, but for the first opportunity, on the bank of the Sava, he decided on the white paintings Hand of Bread (1974), which he placed alongside the embankment on the grass. The same works were placed on the street, where he fixed them with bricks, and in a gallery – but on the ceiling. Showing his paintings in uncommon situations, he demonstrated his viewpoint that although these were paintings, they did not need to untouchable, specially guarded, the artist could act freely with them, not enslaving it in the conventional sense. In this phrase the words were the mean vehicles of meaning and non-meaning. The unclear language collocation contains symbolism in hand, which is connected with work, and in bread, that eternal human need, the resultant of work, and expresses an economic relation. An impression of incompletion is obtained, but there is also punctuation, interventions in red paint, as if on some school task. The interactions that come into being between word and sign in a sense close off the saying: tick – that is good; point – that is that; three lines underlining the words – that needs remembering. Still, this kind of open and incomplete structure seeks a meaningful supplement, it opens up a free field of associations and asks for viewer participation. It is irrational and a little absurd. And precisely here we are in the area of the artist’s interests: the abstruse language although it does gesture at some kind of societal topic, in fact mediates poetic thinking and shows the desire for language to be used non-ideologically.

An interest in language was at the base of most of his earlier works: primarily language related with the visual sign in collages in which he used poetic speech, political and everyday expressions. He researched in differing materials: on paper, plastic foil, fabric, collaged on photographs, papers, comic strips, banknotes, various kinds of consumables like matches and sugar. Often he stuck it all over with sellotape and his handwriting also had a visual quality. In the next phase he was to put these collages into books. The first were one-off works (Will the artist..., Record, both of 1973) and were based on the opportunities provided by plastic transparent pages, through which the contents of the whole booklet could be seen at once, although turning the pages over increasingly reduced it. After these first, he worked on a whole series of books that he reproduced manually. Their simplicity became more marked, and the structure more precise. They were written in pencil on A4 and stapled; most often a few words or a single sentence made their way through the whole book (I want to go home, 1974). The words functioned visually and as signs, sometimes manipulated the meaning of the image, emphasised the reading or even created dissonance among the elements. Most of them like Time (1976), From Language to Language (1977), Two Times (1978), Appropriation of Paper (1978) were based on the use of tautology. In them we are made aware of language, the concrete situation or the actual artistic creation. The meditative tone dominates, deliberation on the material reality the work of art, analysis, articulation, marking and appropriating “one’s own space” within a sheet of paper. The artist withdrew into his private space. Some of them look like poems earlier written that were now broken up into pages (Have a Look 1, 1974). Poetry is to be found in his film Premier 1, 2, 3 (1973), a trilogy of short silent films where the public are asked to read the words and images aloud. In one of these films he decomposed his poem in such a way that in one take there was one word. Since the word was read faster than the duration of the take, the relationship with the previously read word was lost, and at the end, the meaning of actually a very simple poem was lost, for the author was interested in destroying the efficacy of the word with “film time”.

On the other hand, the film in which he shot the signboards on the house in Vlaška ulica from number 62 to 68 (a cooper’s, fresh ice cream, tobacco and so on) he later used for a photographic book made in the form of a leporello. This opened up the whole of an area of interest in street design, that which came spontaneously into being, to which people without any professional knowledge and sign-writers resorted, and which in this socialist country, like that of many professional designers, was at a troublingly low visual level. The artist photographed signs over hairdressers (Hairdressers, 1975) and the windows of artisan photographers (Photographed photographs, 1975), panels in front of restaurants and car repair workshops (Script + Image, 1976), selected examples and presented them.

Since the printing of such books was out of the artist’s capacity, he reproduced them himself, developing photographs by long-lasting work in the darkroom. The order of photographic pages in the leporello takes us back in some of the works to film dramaturgy (Cotton Pad Step, 1975) while some photographic series were previously produced in film, and vice-versa (For Dürer, 1976), or were produced as photographic interventions in the space of the city (Time, 1976). The reasons for this were most often the unavailability of a professional film camera and the price of film. Still, an 8 mm camera and film would always be found for the documentation of actions that went on in various spaces and the exhibitions-actions of the Group of Six that were mainly shot by Mladen and his brother Sven.

Stilinović’s beginnings are an expression of his varying interests, and the way they are interwoven can be seen in almost every individual work, and that was at a time when in Yugoslavia cineastes stuck to film festivals, painters galleries, writers books, and when there was no critical awareness at all of the book as the work of an artist. This intermediality, so characteristic of Fluxus and post-conceptual artists, suited an artist who ranged freely in differing media, without being inhibited by the technical demands of the various artistic disciplines.

The exhibitions-actions of the Group of Six, as the very name says, were a place where the artists not only exhibited their productions but also put on actions that were meant for the particular space, or provoked by them. On Trg Republike (Republic Square) in Zagreb, Stilinović pasted at a tram stop a series of photographs with the smile of a model from a woman’s magazine Burda (1975), past which the passersby were forced to walk, and which they soon defaced. At the same time he handed them out to the passers-by. The minimalist-sensibility assemblage Summer corresponded to the season, and the protected nature of the beach in Mošćenička Draga and the intimacy of the action For U. M. (1976), in which he threw a pebble with a name into the sea – an self-censored dedication, a secret and ephemeral monument. In many actions time had a crucial role. They included the movement of the spectators who took part in the effectuation of the action.

He pasted photographs of a clock – showing 50 different times onto the pavement in different rhythms. If a viewer/passer-by wanted to “catch up with the time” marked on the photos, he was not able to halt and look at them (Time, 1976). The artist was interested in giving the recipient obvious elements, and then confusing and negating them. At the exhibition-action in the New Zagreb estate of Sopot he placed on the pavement between the reinforced concrete buildings, at a distance of a few steps the inscriptions “grass, grass... walking on the pavement forbidden” (1975). And in actions and works done in differing media, there were similar interests and strategies. Linguistic games and the manipulation of language were at the centre of interests. Then he still looked at language and time/space issues and gentle prohibitions, but soon, precisely in language, found an area in which he would express his resistance to the society in which he lived and in which he felt squeezed.

At the end of the seventies he was studying language philosophy reading Mikhail Bakhtin, Rossi Landi, Roland Barthes and other theorists. From Bakhtin, pioneer of modern semiotics, he learned above all that speech was a sensitive indicator of the social and political system, of social and political changes. Bakhtin spoke of language in its life totality, and particularly of language as a “specific ideological system”, “an ideological sign”. Language was a product of the “past work” of a given system, and the language of the then socialist Yugoslavia was for Stilinović the material and instrument of an inexhaustible linguistic capital. He started to use slogans on the theme of work in which production and progress were celebrated, Marxist phrases about the revolution of the working class, metaphors and symbols, particularly the symbolism of red.

One of the artist’s textual works is particularly characteristic of this theme. On pink artificial silk he wrote in red letters: “An attack on my art is an attack on socialism and progress” (1978). He had taken the ready-made formulation “an attack on the achievements of the Revolution is an attack on socialism and progress”, often used in the sacrosanct language of politics, and, switched the roles, replacing one monological expression with another. The difference is in the actor not being the authoritarian state apparatus but an artist with his own feeble voice. There is no interaction here. The socialist phrases did not call for dialogue, on the contrary, often contained a threat clad in revolutionary zeal. And when the artist changed the “collective speech” into the “individual”, it lost its force and became just self-convinced babbling and, indeed, an absurd statement. Making use of irony and paradox, Stilinović took the brutality of this political speech upon himself, and this so-called “abuse” of socialist speech became visible as manipulation. “The issue is how to manipulate what manipulates you, so patently, so brazenly,” wrote the artist in “Footwriting” (1984), “but I am not innocent, there is no art without consequences” (6). Another example is concerned with art. He used the same principle of “replacement” to ask the question of the pertinence of theoretical considerations of the “death of art”, which, long after the famous debates of Heine, Hegel and Heidegger, were renewed in the 20th century, prompted by the expansion of conceptual art in the seventies. The text “There’s talk of the death of art, the death of art is the death of the artist, someone wants to kill me, help” (1977) was also written on pink artificial silk that with its symbolism additionally ironised the substance.

Pink is important to the artist – it is mitigated red, the colour of Rococo, of pleasure and the petit bourgeois, and is against the “communist red” that he was to “exploit” for years. In Red Poem (1975) he coloured various motifs on 90 black and white photographs in red: nail, mouth, wire fence, war monument, people, cigarettes... Colour also takes on various meanings. Then he wrote “Freedom to red”, later on working out in detail this theme that was important for him. The artist was particularly provoked by obtrusive and protected socialist symbols, and one of these untouchable taboos in the socialist country was, certainly, red. The works about the de-symbolisation of red – although they made use of a tautological structure, like Consumption of Red (painting on which this text was written in red), Auction of Red (an auction of a painting on which in red was written Auction of Red), My Red (a series of photographs in which the author cuts open his finger with a razor blade and writes on his hand with his blood), Whited Red (a box with red paint to which white is added) – were not only analytical and self-reflexive works, but anarchic and cynical revolt against the social symbolism. Auction of Red is a tautology for the author put to auction the red painting, but he changed a “socialist” into an absurd reading. The experience of colour, thought Stilinović, should be individual, but this ideologisation constantly deprived it of this. (7) But we already know that the artist is not innocent. He appropriates red and does with it what he wants; he likes tautology, this familiar figure of conceptualism, elementariness, repetition and humour as well. The identity of red is explained in words, materials and works. And all this is brought into question. Ideology is omnipresent, and the artist plays multiple games with it.

He brings red into the “system of art”: at the opening of the Biennale of Venice in 1976 he exhibited for 10 seconds at the Yugoslav Pavilion a piece of paper on which he wrote in red pencil “Red at the Biennale”. Through his own blood he brought red into the discourse about art in an environment Art is.... in the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb in 1977, where, seated at a table in a room full of definitions of art written out on pieces of paper hung on the walls he wrote in his own blood sentences such as “I bleed over this book”.... “letters written in blood”... truthful and logical statements that refer to nothing but themselves. Then he went on with rather grandiloquent sentences: “no art without blood”, “my life is written in blood”, “it’s all in the blood”, which in the traditional artistic jargon are connected with creation, of the kind that the artist shrank from. Among the many definitions of art that he took from the best known aesthetes, from the book of Guido Morpurgo Tagliabue Contemporary Aesthetics, the artist wrote some other “problematic definitions”, which also referred to the material that he worked with and the actual process of writing. For the artist, unlike the philosophers who always dealt with big topics, always presents the process and situation here and now. “Each of these sentences,” wrote the artist in an informational pamphlet that he left in the room after he had ceased writing the book “relates to my work by showing how the work can be interpreted (manipulated). According to my opinion the work has to count on manipulation, and that appears here as a component part of the work and creates a whole with it.” It might be said that here it was to do with the artistic being terrorised by art theory, which the artist jokingly resisted.

Rejection of respect for the external emblems of the state – the flag and the currency, mocking and confronting the authorities with the help of their own symbols were characteristic of Stilinović and of other members of the Group of Six. Mladen in Double Offence (1980) painted the Yugoslav flag over banknotes, creating an irritance with his disobedience to two laws: one that prohibited making free use of the flag and another that banned defacement of the currency. He wrote texts across banknotes in his blood, wrapped up bread in money, made collages with banknotes... Sven Stilinović painted the flag in black and white only, and patched it up out of wooden planks and cotton wool (1984-1985); Vlado Martek in his actions sold money for half its value (1980) and walked along the street waving a hairy (pig bristle) flag (1983). The quite frequent invocations of Bakunin and his predecessors Proudhon and Stirner, as well as to De Sade, and quotations from them, particularly in the works of Sven Stilinović, referred to the libertarian traditions that could be sensed in the Group. Freedom of creation and freedom of behaviour, autonomy of the individual vis-à-vis the state and resistance to all the powers that took from people the right to arrange their own lives according to their own needs were felt as a priority. Humour was important to all of them, but their works were nonetheless subversive. Indeed, with some actions politics as institution was “smashed”. For where resistance appears, the system itself is jeopardised. Every initiative was able to work as an example and to involve other actions too.

Outside exhibitions-actions were an occasion for talk about art with a public that otherwise would never have gone into a gallery. This experience was important for them, for they saw in it a possibility for the expansion of their artistic and their social engagement. It was important to shake off the prohibitions that held people back, to get free of value judgements that inhibited artistic work, to enable the work to prove itself and be tested out. Extempore on the whole one-day exhibitions-actions of the Group of Six Artists expressed their romantic aspiration to be able to use art to change life and art, not to submit to any demands and rules of the system, nor any kind of inherited artistic conventions. They had the guerrilla style, the tactic of discomposure, or rebellion in little, full of critical spirit, at once mocking and joyful. The public, which could not cope very easily with this, asked them many questions, which they had not even posed themselves. In these exhibitions and actions art brought life back to the streets. How important the dialogue with the public was is shown by the number of conversations that were held in galleries, unconnected with any exhibition of works. (8) They were interested in the relationship of artist and artwork to the public, not just the work-public relation. At the exhibitions-actions they would distribute the journal May’75, which the Group of Six started publishing in autumn 1978.

The street was thus a site that offered multiple challenges. They could communicate with the public via their art in real time, with actions that represented their manner of living. Art for them was not an avocation nor were the exhibitions-actions just the presentations of their material productions. In works in consumable materials, negligently produced, meant for exhibition on the pavement, as well as their behaviour, they certainly threatened the traditional concept of art. Although it was not to be toppled, they could at least shake it. Their some 20 or so exhibitions-actions meant primarily a revolt, the occupation of space and the taking of the freedoms that irrevocably belonged to them; with them the Group of Six opened up its path. They pared down their artistic positions and highlighted their moral viewpoints.

At the beginning of the eighties several older and younger artists joined the Group at the exhibitions-actions, but after the opportunity for exhibiting in the Podroom gallery space appeared, exhibitions-actions outdoors were gradually played down. The first exhibition of characteristic title For an art in the mind brought together 18 artists from Zagreb, on the whole conceptual and post-conceptual in orientation, a whole front of the New Art Practice. Podroom was a typical alternative gallery with hardly any budget at all, in which the artists did everything themselves, including running off the catalogues by hand. During 1978 and up to the beginning of 1980, Podroom was an important gathering place, a place for exchange of ideas, and after that the art activity went on in the next important place – the Extended Media Gallery (PM Gallery), which Mladen Stilinović ran for ten years.

The reception of art of this kind in our setting did not meet with very wide approval. The media were on the whole regularly hostile, sometimes fiercely so with political accusations and personal insults (9) but in fact there were no real consequence for the artists. They did not have the artistic perks characteristic of the socialist countries (they were not given studios or public commissions) but they were not persecuted. Some institutions in Zagreb and Belgrade continuously followed their activities, with competent enthusiasm, and abetted their exhibitions abroad. In 1977 Stilinović exhibited at the 10th Youth Biennial in Paris, as well as at the exhibitions in Frankfurt, Modena, Warsaw and so on. They obtained direct invitations to international shows. One of the most important of the time was Works and Words, organised by the De Appel Gallery in Amsterdam in 1979, featuring artists from The Netherlands, Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. (10) Stilinović met his opposite numbers from Eastern Europe and for the first time he performed before a western public. Challenged by this situation, he held The Discourse about Language and about Power, and the performance The Foot-Bread Relationship. Both actions were -anti marked. Aware of the domination of English, he gave a lecture in Croatian, against English. It was clear that English was the language of globalisation, “that history is ‘written’ in English, that belonging to the interest, political and economic spheres that communicated in this language meant ‘real’ existence on the map of the world, a language in which currently the greatest power is manifested” (11) and so he raised his reedy voice. In the public there were artists from the former Yugoslavia who were of course the only people to understand and to laugh at the lecture.

The performance did not consist of kicking a loaf, which we know from the series of photographs called Foot-Bread Relationship (1977). He came onto the stage with bread under his arm, stuck up photos of kicking a loaf on the wall, put the loaf on the floor and stood by it about a minute. The performance analysed the frequent practice of artists in which the ultimate result of the performance was in fact photographic documentation. Well, then, wondered they artist, why put on a performance in front of an audience at all? He waved his leg and stopped....

Translated by Graham McMasater

Publisded in Mladen Stilinović – Sing! (ed. Branka Stipančić), Ludwig Museum, Budapest, 2011

1) Mladen Stilinović in the interview “Život znači ne ići na dvor”/”Life means not going to the court”, in the catalogue Umetnik na delu – 1973 – 1983 / Artist at Work – 1973 - 1983, Gallery SKUC, Ljubljana, 2005, p. 37.

2) Texts on contemporary art were available through numerous translations printed in journals such as the Zagreb Pitanja, Rijeka Dometi, Polja from Novi Sad, the Belgrade Treći program, Delo, Filmske sveske, Rok (mainly with complete disregard for copyright and royalties).

3) Happening took place at the 24th May Festival of Student Theatres in the ITD Theatre. As well as the group Pan 69 there were artists from Slovenia, Nuša and Srečo Dragan and a few friends. With music we went into the hall, carried banners, gave out flowers, sat on the stage, ate and drank. The baton was carried, one person played Tito. Then the curtain dropped and interrupted the show. At the end knives were meant to be handed out. The idea was that May and Other Rituals ‘68 be shown: the Mayday celebration, the long relay run and rally celebrating Tito’s birthday, the student demonstrations, after which came two Tito speeches – the first that was well-disposed to the students and the second in which he furiously accused them – after which came the expulsion of students and other rebels from the Party, and of course, the reception of new members, for the mechanism had to work. No one could touch on the topic of Tito. This was surrounded by rules and fear. Luckily, apart from one “informative conversation” nothing happened to those who took part in the happening. The visual arts were pretty well spared. Cineastes and writers went down.

4) FAVIT is an abbreviation for Film, Audio, Video, Research, Television, which presented the sphere of work and interests of an informal group set up at the Croatian Film Clubs’ Association in 1973. Film author Vlado Petek was the main generator of the joint actions that were called multivision. They used a fairly large group of technical devices and screened in parallel films and slides. Within FAVIT, Mladen produced the audio-visual collage Reign of Terror of the Image, using slides and parallel projections of his 8 mm and 16 mm films and sections from cartoon, erotic and documentary films, as well as a TV broadcast.

5) It is important to mention that although the neo-avant-garde group Gorgona (1959-1966) was chronologically prior to the generation of conceptual and post-conceptual artists, these artists were to a large extent unknown to the generation of artists that, like Stilinović, was formed in the late sixties and in the seventies. There was a caesura between 1963, when they stopped the exhibitions in Studio G (Gorgona) until the Gorgona retrospective in 1977 in the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, when for the first time it was possible to see a largish quantity of their works and understand what it was about. Then there was some interaction between the old (Mangelos, Kožarić and Knifer) and the younger generation.

6) Mladen Stilinović, “Footwiting”, in the catalogue of his solo show, Studio of the Gallery of Contemporary Art, 1984, no pagination.

7) He wrote about this in the text “Consumption of red-pink” in the catalogue of the individual exhibition Red-Pink in the Podroom in 1979. “Taking red through various contents, I want to de-symbolise it, make it just a colour. Thus the effort, if we want to read the painting correctly, consists of wiping out our knowledge, and not in confirming it. If we want to read the work through knowledge of this colour, there will be an absurd reading. Since we cannot hide knowledge, the works are read as symbols and de-symbols.”

8) Actions of the Group of Six: on New Year’s Eve in the Skyscraper Passage, Zagreb (1977), Oral tradition in Nova Gallery and the SKC Gallery, Belgrade (1978).

9) On the occasion of the 10th Youth Biennial in Paris, in the article “Between terrorism and destruction” in Oko, November 17, 1977, Zrinka Novak wrote: “Certainly, these exhibitions of the Paris Biennial – incorporating without any conflict the endeavours of exhibitors from our country – are today more interesting to sociologists, speech therapists and even psychiatrists than to those who in any way deal with visual phenomena... Everything that I looked at going round the exhibition was violence, was destruction. No one actually hijacked a plane, but still this, I think, is the real basis, the ideational basis of the terrorism of the young: the conviction that it is all a lie, and that everything has to be pulled down.” Stilinović had exhibited the white paintings Hand of Bread and five books: I want to go home, Time, Now, Disorder, Written in Blood.

10) The following exhibited: Gábor Attalai, Gábor Bódy, Miklós Erdély, Tibor Hajas, Dóra Maurer, Endre Tot, Jerzy Beres, Jan Mlcoch, Petr Štembera, Tomislav Gotovac, Sanja Iveković, Dalibor Martinis, Raša Todosijević, Zofia Kulik and Przemysław Kwiek, Józef Robakowski, Zbigniew Warpechowski, Ryszard Waszko and others.

11) Mladen Stilinović in the interview “Opera Pain” in the catalogue Pain, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 2003, p. 18.

TADEJ POGAČAR

School’s Out was originally conceived in 1997 as a participatory site-specific project in which the students of the Šentvid Gymnasium in Ljubljana were active participants. Discreet installations (featuring teaching materials, instructional aids, everyday objects, etc.) were set up in a number of classrooms; they problematized the issues of knowledge, student–teacher relations, instruction, discipline, and control.

The School’s Out series of works (1997–present) were created out of a desire to explore the modern history of schoolteaching through subjective visual memory. To this end, they use archival images from the 1940s, 1960s, and 1970s (borrowed from the Slovene School Museum), which depict the processes of school instruction, discipline, control, and so on, in juxtaposition with objects and collages. These objects are educational tools and aids that point clearly to the time of their origin, namely, the period of socialism and the common state of Yugoslavia (e.g. a triangle with its centre cut out in the shape of Yugoslavia, maps, etc.); the collages, meanwhile, thematize classifications, visual structures, colour systems, fragments of illustrations from textbooks, and the like. The narrative strategy applied in the collages is based on the use of repetition, empty space, nonsense, clichés, and humour.

Daily Life as Public Practice in the Field of Multiplicity

The productions and interventions of Tadej Pogačar at the end of the first decade of the New Millennium.

Miško Šuvaković

Tadej Pogačar is an outstanding example of a contemporary artist who appears and expresses himself in the antagonisms and contradictions of shaping life experiences in the here-and-now or the there-and-then on our global map. He is on the move. He changes topologies. Pogačar is an example of a global artist, because he manages to work with singular samples of thoroughly differing segments of everyday life in various geopolitical, geo-cultural and geo-behavioral spatial situations, worldwide.

Pogačar’s “artistic activity” is simultaneously based on the programming and execution of ambiguous effects in the fields of institutions or forms of daily living by means of realization of artistic and activist intentions. His intentions, however, are not a simple orientation of an artist towards the act of creation of a work of art as a completed art piece. Pogačar also engages in curating and para-curating activities. He intervenes with models of inhabiting and usurping institutions within the art world (museums, galleries, a flat of a fine art critic), associations and culture (urban quarters, syndicates of sex workers, associations of the homeless). Pogačar works with a activist-like demonstrative confrontation with the mechanisms of daily existence in the urban dynamism of singular life in the global net of contemporaneity. Forms of everyday life are his “post-medium” of intervention activity. However, he also curates a gallery and publishes artist’s books and theoretical works on contemporary artistic practices. He classifies and exhibits indexes of “affects” and “auras” within contemporaneity. His work in all these different instances is subject to permanent re-articulations not connected with a “finished artwork”, rather with affective and auric intensities of boundaries between intensity and non-intensity in the everyday existence of an entirely ordinary human life. He is attracted to the “trivial situation”, although he does not search for the phenomenology of obscene triviality, rather the politics of obscenity in normal and entirely trivial everyday lives of ordinary people worldwide.

Pogačar’s work is, therefore, most frequently accessible in the duality of (1) a random live interactive event, and (2) a documentary mediation of such instigated, performed and completed events. The event itself, and the documentation, are the operational tools with which Pogačar, as an artist and a curator, that is, an activist, implements an informational intervention in the field of social activity. His work is, in its essence, a type of activist existentialism, in other words, an analogy to interventive cognitive mappings that originated and developed in Situationism. He, most definitely, does not perform a remake of 1960s Situationism- Pogačar is absolutely an artists of a different era, the epoch of globalization. Tadej Pogačar works within the “envelopes” and/or “frames” of situations that have global topologies.

It is of utmost importance, for Pogačar’s work, to point out the significance of “relations”, that is, the establishing of relations within heterogenous planetary daily lives. This is why his procedures can be read through the theorization of “relational aesthetics” and models of “postproduction” of Nicholas Bourriaud. His projects are about global cultures in which the relationship between art and social practices is open and relative to changes in potential relations of the singular and the universal. In Pogačar’s work, traces or models of cultural relations are presented as representatives of everyday forms of life. His artistic productions- for example, projects like Different (small) pieces of rubbish (2010) or Public Sculpture (2010)- indicate that art, as practice, transfered into the field of dematerialized work, that is, artistic practice in a gaseous state of the impact of the affect derived from the interplay of relations, denotes the internal and external dynamism of life situations. These processes, the ones unfolding in the midst of urban daily culture, create a strong and illusive sensation that the trace of human existence is everywhere, that it has to be everywhere. This is why only practice as practice exists. Thus, Pogačar is connected, in fascination, with the concept of practice. The effects of its aura appear. We are dealing with intensities instigated through action in a particular context, and effects of different intensities in the shaping and reshaping of life in institutions, human habitats, dumping grounds, central spaces of public life, and marginal situations of being. Pogačar works- he shows and exhibits- these complex potentialities of the public and private, in other words, the marginal and the central in framing “being” within contemporary daily life. It is as if he, in this way, finds alternatives within contemporary “empires” of politics, economy, bio-technologies- as if he searches for the potentialities of the field of otherness which is the source of critical activity. His research indexes and projects potentiality of real democracy for “an individual form of life!” amidst other forms of life. He is focused on the importance of singular existence in the multitudes that change in the fight for survival in the middle of an ordinary and common daily life, here, all around us, and amongst us. The individuality of the democratic act- direct democracy- demonstrates that he is an artist of the politics of singularity.

ART AL QUADRAT

LIMBO ECONÓMICO EN TRES ACTOS. Art al Quadrat

Limbo económico en tres actos refleja cómo dentro del sistema capitalista se produce una inversión fallida de excedentes, lo que genera un limbo económico, a partir de tres historias personales correspondientes a diferentes generaciones y periodos de la historia reciente española.

PRIMER ACTO: EL AHORRO

La obra expone 7.719,50 pesetas, en billetes acuñados entre 1925 y 1936, ahorradas por una familia española, que se guardaron como un tesoro dentro de un saco de tela. Este dinero quedó sin valor con la irrupción de la dictadura franquista y el nuevo cambio de moneda. El periodo coincide con el final de la Guerra Civil, en la que muchos ciudadanos guardaron sus billetes usados en la República por si en algún momento volvían a tener valor.

En la instalación se muestra cómo este dinero, lleno de figuras mitológicas, alegóricas, personajes históricos y de la cultura, con valor patrimonial en su origen pero ya sin valor económico, vuela sin sentido y sin rumbo impulsado por dos ventiladores dentro de un tubo transparente con un texto en el que se explica cómo y por qué ahorrar, sacado de la cartilla de ahorro guardada junto al tesoro.

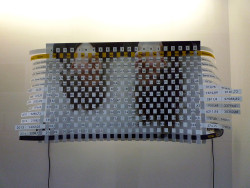

SEGUNDO ACTO: TRIPLE INVERSIÓN

Por otra parte, en el segundo acto se muestra una triple inversión en el seno de nuestra propia familia, que realizó tres colecciones de sellos idénticos entre los años 1987 y 1998 de Filatelia Española: una para cada hija. La inversión se realizó pensando en que el dinero, excedente de lo ganado en la empresa familiar, tendría mayor valor en un futuro; sin embargo, la devaluación de estos sellos por la moda de las colecciones atesoradas por familias de clase trabajadora venidas a más, como en el caso de la nuestra, hace que con el paso de los años la colección no cueste más que el precio que cada sello representa, e incluso menos para los coleccionistas.

En la instalación se exhiben tres tubos en los que dentro se mueven, también a través del viento de un ventilador, las tres colecciones de sellos. Detrás de estos, se muestran tres fotografías de los sellos que, pese a que parecen iguales, cada una corresponde a una colección.

TERCER ACTO: AUTOINVERSIÓN

En el tercer acto, se habla de nuestra propia inversión en el trabajo artístico que realizamos y en el que utilizamos nuestros recursos económicos para invertirlos en nuestra obra. Se muestra un cambio en el sentido de la inversión y la rentabilidad, sin olvidar el origen de la inversión en educación que nos dieron nuestros padres y los ahorros familiares que nos permitieron empezar a hacer obra. Pese a la poca rentabilidad, nos movemos entre la motivación y el convencimiento personal de que nuestra autoinversión va más allá de un limbo: representa una forma de vida.

En esta obra se incluye una fotografía actual de las componentes de Art al Quadrat invertida que se entrelaza con un documento de cálculo donde se realiza un cómputo de la inversión realizada de toda la trayectoria del grupo artístico. Un ventilador colgado del techo moverá la fotografía.

Art al Quadrat, 2002 (Gema y Mònica del Rey Jordà, 1982). Son licenciadas en Bellas Artes y tituladas en el Máster en Producción Artística por la UPV. Han recibido diferentes becas de creación e investigación como la beca Habitat de Castellón (Ayuntamiento de Castellón, EACC) 2013-14 (G), la Cátedra Arte y Enfermedad 2013, la beca FPU 2008-12 (M) y la participación el II Encuentro de artistas nuevos de la Ciudad de la Cultura de Santiago de Compostela 2012, entre otras. Exponen individualmente en la Galería Coll Blanc de Culla en 2012, Sala La Llotgeta en Valencia, 2014, y Casa Elizalde en Barcelona, 2014. Destaca la participación colectiva en las exposiciones Becas Hábitat. EACC, 2014 (G). Empatía. Diálogos con y desde la enfermedad. Centro Párraga. Murcia 2014 y Cool Stories III con itinerancias en Swiss Architecture Museum Basel‘11 y Lincoln Center, Parsons School of Design New York‘11, entre otros.

Publication