space #1 - gallery

space #1 - gallery

POÉTICA Y POLÍTICA

Estrategias artísticas en la neovanguardia húngara

Podríamos establecer el inicio de la narrativa de la neovanguardia húngara en los años centrales de la década de los sesenta, cuando dos jóvenes poetas, Gábor Altorjay y Tamás Szentjóby, decidieron organizar en un sótano de Budapest el primer happening celebrado en Hungría (The Lunch. In Memoriam Batu Khan, 1966). El histórico y escandaloso acontecimiento, que acabó en interrogatorios policiales y fue censurado por el aparato del Estado, partía de conceptos como la sincronicidad, la progresividad y la radicalidad, así como de la vocación de formar parte de la vanguardia contemporánea internacional. A pesar de sus posturas diferenciadas y heterogéneas en relación con el uso de los medios y de unas estrategias que reflejaban de diversas formas las condiciones políticas existentes tras el Telón de Acero, aquel nuevo arte progresista húngaro ahondaba en la tradición de pertenencia al mundo del arte contemporáneo «occidental». En el periodo que va de finales de los años sesenta a la mitad de la década de los setenta, las prácticas vanguardistas húngaras continuaron oponiéndose a la oficialidad y mostraron gran simpatía por las tendencias vanguardistas internacionales.

El contexto político-cultural en el que surgió aquel nuevo arte animaba a los artistas jóvenes a establecer programas existenciales y artísticos paralelos. Mientras el partido socialista en el poder empezaba a construir su propia versión oficial de la modernidad sobre el tabú de la revolución sofocada en 1956, los jóvenes, que mostraban una actitud antipolítica y compartían un tipo de representación generacional, rechazaban totalmente aquel enfoque, encontrando —a pesar del aislamiento cultural— formas de intercambio de información, forjando redes cada vez más internacionales y adquiriendo sus primeros jeans en algún otro país socialista amigo. En 1968, ese creciente círculo underground compartía con sus homólogos internacionales el mismo bagaje representacional y, en algunos casos, descubrió el potencial de solidaridad desplegado con ocasión de la reciente invasión de Checoslovaquia, virando hacia un izquierdismo políticamente radical.

La necesidad de compartir estrategias y de contar con un marco institucional se evidenció con la celebración en 1968 y 1969 de las primeras exposiciones colectivas de la neovanguardia. Como ocurriera con el primer happening, la escena artística progresista actuó por fuera de las instituciones canónicas oficiales, creando espacios propios en clubes juveniles semioficiales y marginales, viviendas particulares o centros culturales de los suburbios. Además de generar frustración entre los círculos de artistas, la ausencia de galerías, de crítica de arte y de estructura institucional dio lugar a una narrativa distorsionada, en la que la neovanguardia se vio durante décadas incapaz de encontrar su lugar. De hecho, el interés internacional por la vanguardia húngara que hoy constatamos continúa enfrentándose al problema de la existencia de unas narrativas no escritas y de una investigación en marcha que lucha por reubicar aquel periodo progresista.

En términos artísticos, durante los últimos años sesenta se produce en Hungría un giro conceptual que hizo que incluso artistas vinculados a la pintura abordaran la cuestión de la desmaterialización de la obra de arte. Tras los experimentos iniciales con la poesía visual, la poesía de acción y la semiótica, a los que siguieron los primeros eventos y objetos de Fluxus, la investigación lingüística representada por Joseph Kosuth y por el colectivo Art and Language llevó a grupos de creadores hacia las prácticas conceptuales. Los nueve artistas seleccionados para esta exposición comparten interés y motivación por los nuevos medios y prácticas lingüísticas del arte conceptual, aunque sus espectros individuales y sus focos de atención surjan de fuentes heterogéneas y de bagajes teóricos individuales.

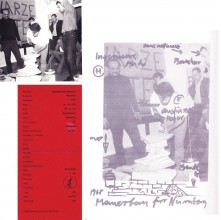

En 1967, un año después del primer happening, Gábor Altorjay se fue a vivir a Alemania Oriental, donde se integró en el movimiento de vanguardia accionista representado principalmente por Wolf Vostell y su círculo. Inspirándose en la crítica social e institucional del arte político alemán, estrechamente relacionado con los acontecimientos de 1968, Altorjay produjo unos objetos radicales y poemas visuales Fluxus que, desde el punto ideológico, partían de un rechazo doble: al Capitalismo y al Comunismo de la Europa del Este. En línea con ese contexto, las obras de Altorjay acusan la energía crítica del 68, oponiéndose a instituciones artísticas canónicas como Manifesta o la Feria de Arte de Colonia. Para esta última Altorjay organizó, junto al círculo de Vostell, un anti-evento titulado Fünf Tage Rennen, concebido como alternativa al arte orientado al mercado.

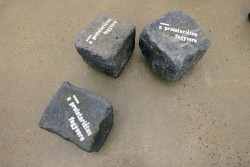

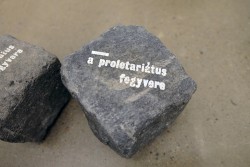

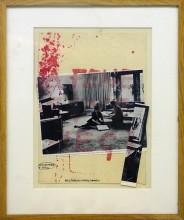

Tamás Szentjóby, que tenía prohibido viajar como consecuencia de un intento fallido de emigrar, permaneció en el país, contribuyendo al panorama artístico húngaro con happenings y acontecimientos de Fluxus que pronto le llevarían a convertirse en icono del underground húngaro. Aunque sus primeros poemas fueron bien acogidos por las figuras más veteranas de la poesía moderna, en torno a 1966 rompió con la lírica de la modernidad y creó los primeros ejemplos húngaros de collages y poemas visuales. En el marco del Parallel Course Study Track (1968), su programa universal-pedagógico de vanguardia que tuvo un análogo coetáneo en la actividad de Joseph Beuys, Szentjóby proponía alternativas para cambiar todos los aspectos de la realidad. Dos ejemplos de esta serie abordan el tema de la reforma de las instituciones artísticas (los modelos de museo) y también la esfera privada y su representación. Los poemas visuales de Szentjóby se exponen por primera vez desde la retrospectiva de 1975 que precedió a su marcha de Hungría.

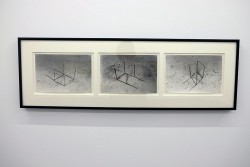

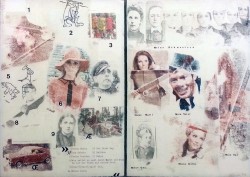

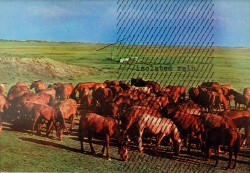

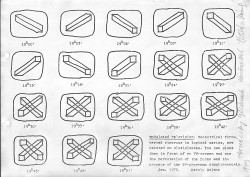

Los miembros de la emergente escena artística de la vanguardia húngara (incluyendo al propio Szentjóby) están presentes en una fotografía de Dóra Maurer titulada Once We Left (1972), una foto-acción que formó parte de la serie de eventos llevados a cabo en el Studio Chapel de Balatonboglár, donde durante un periodo de tiempo este grupo de artistas pudo escapar a la censura. Con su énfasis en la fotografía, el cine, el diseño gráfico y la pintura, la producción de Dóra Maurer, en la actualidad una de las artistas húngaras de mayor renombre, propone al espectador nuevas posibilidades para recombinar motivos en el espacio y el tiempo. Las obras de Maurer que aquí se muestran ofrecen los primeros indicios aparecidos en su práctica artística de un marco conceptual de pensamiento que abarca desde las estructuras gráficas a la fotografía.

Si Dóra Maurer nunca reflexionó en su obra sobre cuestiones de género, en el otro extremo se encuentra Katalin Ladik, yugoslava de nacimiento y primera mujer artista en plantearse en Hungría el cuerpo como soporte de su creación. Activa tanto en Hungría como en Yugoslavia, Ladik, que desde fines de los sesenta practica un body art ritual de base poética, es también conocida internacionalmente por su poesía fónica. En compañía de Bálint Szombathy y de amigos artistas yugoslavos, Katalin Ladik creó Bosch+Bosch Group, un colectivo experimental que se fundó tomando como referencia los valores de la vanguardia clásica. El teórico del grupo, Bálint Szombathy, emprendió una investigación teórica y realizó interpretaciones políticas de los discursos de la vanguardia contemporánea.

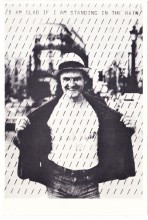

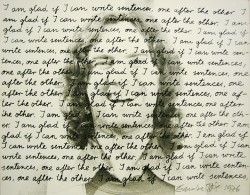

Endre Tót rompió drásticamente con la pintura en 1971. Desde entonces se ha centrado en el arte conceptual, implicándose en corrientes internacionales como Fluxus o el Mail Art. A comienzos de los setenta desarrolló algunas de sus ideas básicas, como «Nothing/Zer0» o «Rainsand Gladnesses», que impregnarían la actividad que desarrolló en Alemania en las décadas siguientes. Estos trabajos se encuentran entre las manifestaciones más tempranas del arte conceptual en la Europa del Este, y abordan grandes preocupaciones filosóficas y universales. Sobre Endre Tót un compañero de Fluxus, Ken Friedman, escribió en el catálogo Who’s Afraid of Nothing (1999) del Museum Ludwig: «Las piezas de código cero de Endre Tót proponen una voz distinta y personal sobre la vacuidad del vacío, algo que ningún otro artista ha hecho como él. Ahí radica la genialidad y la importancia de Tót».

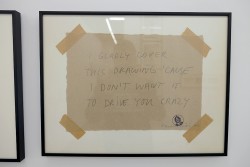

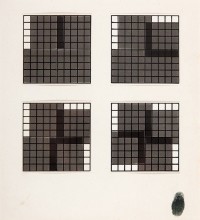

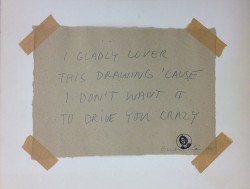

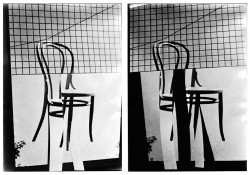

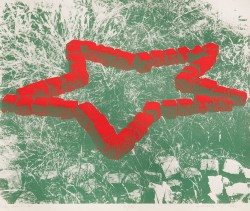

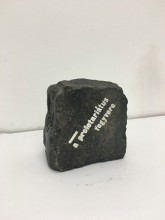

El enfoque del Taller de Pécs (Pécsi Mühely), fundado en 1970 en esa ciudad húngara, bebió en la tradición de la Escuela de la Bauhaus, en el legado de la pintura y las artes gráficas locales y en las tendencias internacionales del arte conceptual. La singular aproximación a la fotografía de tres de sus miembros, presentes en esta muestra —Ferenc Ficzek, Károly Halászand y Sándor Pinczehelyi—, se mueve entre una reconceptualización de temas clásicos de la fotografía (como la sombra, la luz o el espacio), la representación del yo y reflexiones críticas sobre los símbolos del socialismo. La idea de conservar y mantener el arte fuera del espacio de la institución —en otras palabras, en el dominio privado de la libertad que le es propio— plasmada en la instalación-museo de Károly Halász, sirve de ilustración de las dimensiones críticas y poéticas de la neovanguardia húngara.

Emese Kürti - acb ResearchLab

POETICS AND POLITICS

Artistic Strategies in the Hungarian Neo-Avantgarde

The narrative of the Hungarian Neo-Avantgarde can be traced back to the mid-sixties, when two young poets, Gábor Altorjay and Tamás Szentjóby, decided to organise the first happening in Hungary (The Lunch. In Memoriam Batu Khan, 1966) in a cellar in Budapest. The scandalous symbolic event, which led to police interrogations and censorship from the part of the state apparatus, was predicated on the ideas of synchronicity, progressiveness, radicalness and the wish to belong to the international contemporary avant-garde network. Despite their differentiated and heterogeneous positions regarding the use of mediums and the strategies engaging with the surrounding political conditions behind the Iron Curtain, the emerging progressive Hungarian art scene carried on the tradition of being part of the contemporary “western” art world. During the late sixties and mid-seventies, Hungarian avant-garde practices had their continuation in the opposition to officialdom and in a strong affection towards international avant-garde tendencies.

The cultural-political context in which the new art emerged urged young artists to set up parallel existential and artistic programmes. As the consolidated socialist party started to build up its own official version of modernism, covering over the taboo of the repressed revolution in 1956, the young generations with an anti-political attitude and with a common generational representation totally rejected this programme. Despite being culturally isolated, they found ways of exchanging information, building up increasingly more international networks and buying their first jeans in some other friendly socialist country. By 1968 this growing underground circle was engaging with the same representational baggage as their international counterparts. Some of them, harnessing the potential of solidarity with the recent invasion of Czechoslovakia, turned towards a politically radical, leftist attitude.

When the first group exhibitions of the neo-avantgarde were held in 1968 and 1969, the need for collective strategies and an institutional framework was articulated. Similarly to the case of the first happening, the progressive art scene acted outside the canonical institutions of the official domain, and founded its spaces in semi-official, marginalised youth clubs, private apartments and suburban cultural houses. The lack of galleries, art criticism, and an institutional framework caused not just frustration in artists’ circles but also produced a distorted narrative, in which the neo-avantgarde would not find its position for decades. The current international interest in the Hungarian avant-garde still faces the problem of unwritten narratives and ongoing research which strives to reposition this progressive period.

In terms of art, the late sixties marked a conceptual shift in Hungary, when even those artists who were still engaged with painting, faced the issues of dematerialization of the artwork. After the first experiments in visual poetry, action poetry and semiotics, followed by the first Fluxus events and objects, the linguistic research represented by Joseph Kosuth and the Art and Language group inspired groups of artists towards conceptual practices. The nine artists selected for this exhibition share a common interest and motivation in the new mediums and linguistic practices of conceptual art, although their individual spectrums and focuses have their own heterogenic sources and theoretical backgrounds.

In 1967, one year after the first happening, Gábor Altorjay left the country for East Germany, where he joined the avant-garde actionist movement hallmarked most of all by Wolf Vostell and his circle. Inspired by the social and institutional critique of German political art, strongly connected to the events of 1968, Altorjay produced radical Fluxus objects and visual poems with the ideological background of a double negation of Capitalism and Eastern Communism. In accordance with this context, Altorjay’s works bear the critical impetus of 1968, opposing canonical art institutions like Manifesta, or the Cologne Art Fair. For the latter, Altorjay, together with Vostell’s circle, organised an anti-event called Fünf Tage Rennen to offer an alternative to market-oriented art.

As he was banned from travelling because of an unsuccessful attempt to emigrate, Tamás Szentjóby stayed and shaped the Hungarian avant-garde art scene through happenings and Fluxus events, and soon became an underground icon. His first poems were well received by the elderly representatives of modernist poetry, but he broke with modernist lyrics around 1966 and produced the first examples of collages and visual poems in Hungary. In the framework of its universal-pedagogic avant-garde programme, the Parallel Course Study Track (1968), which had a contemporary analogue in the activity of Joseph Beuys, Szentjóby proposed alternatives for changing every aspect of reality. The two examples from this series deal with the issue of reforming art institutions (museum models) and the private sphere and its representation. Szentjóby’s visual poems are exhibited for the first time since his 1975 retrospective exhibition, after which he left Hungary.

The members of the emergi ng avant-garde art scene in Hungary (including Szentjóby himself) can be seen in Dóra Maurer’s photo action Once We Left (1972), performing an action in the series of events held at Studio Chapel in Balatonboglár, where they were able to act without censorship for a while. With its emphasis on photography, film, graphic design and painting, the work of Dóra Maurer, one of the most renowned Hungarian artists, opens new possibilities for the viewer to recombine motifs in space and in time. Her pieces on display in this show marked the first signs of a conceptual way of thinking in her practice, from graphic structures to photography.

While Dóra Maurer never reflected on gender considerations in her oeuvre, on the other pole from this perspective, the Yugoslavia-born Katalin Ladik was the first woman artist in the country to regard her body as a medium for her art. Active both in Hungary and Yugoslavia, Ladik has been performing ritualistic, poetry-based body art since the end of the sixties, also earning a name for herself internationally through her phonic poetry. Katalin Ladik, together with Bálint Szombathy and some artist-friends from Yugoslavia, formed the experimental Bosch+Bosch Group, founded on the values of the classical avant-garde. Bálint Szombathy, the theoretician of the group, initiated semiotic research and political interpretations of the discourses of the contemporary avant-garde.

Endre Tót broke radically with painting in 1971 and ever since he has been preoccupied with Conceptual Art, as well as being involved in the international Fluxus and Mail Art movements. In the early seventies, he evolved some of his basic ideas like “Nothing/Zer0”, “Rains and Gladnesses”, which permeated his activity in subsequent decades, spent in Germany. These works, some of the earliest manifestations of Conceptual Art in Eastern Europe, engaged with broader philosophic and universal concerns. As his Fluxus colleague Ken Friedman wrote about him in the Museum Ludwig catalogue Who’s Afraid of Nothing (1999): “Endre Tót’s zero-code pieces give a discrete and particular voice to the emptiness of the void. No other artist has done this in quite the same way. This is Tót’s genius and his importance.”

Founded in 1970 in the city of Pécs, the approach of Pécsi Mühely (Pécs Workshop) was influenced by the tradition of the Bauhaus school, the legacy of local painting and graphic art as well as international tendencies in Conceptual Art. The unique vision on photography of three of its members featured in this show—Ferenc Ficzek, Károly Halász and Sándor Pinczehelyi—range from the reconceptualization of classic photography-related issues like shadow, light and space, through the representation of the self to the critical reflections on the symbols of socialism. Maintaining art outside the spaces of the institution—in other words, in the private realm of freedom, where it belongs—Károly Halász’s museum-installation gives good account of the critical and poetic dimensions of the Hungarian neo-avantgarde.

Emese Kürti - acb ResearchLab

Publication