space #1 - gallery

space #1 - gallery

+Info Artist

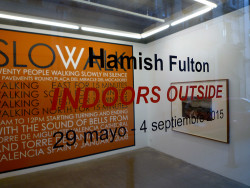

HAMISH FULTON

INDOORS OUTSIDE

29 mayo - 4 septiembre 2015

Inauguración 29 mayo 20h.

Acción Colectiva / Communal Walk:

30 mayo 11:30h.

espaivisor presenta del 29 de mayo al 4 de septiembre de 2015 la tercera exposición en la galería del artista inglés Hamish Fulton (1946), después de sus exposiciones en 2005 y 2008. Con un trabajo que se enfrenta a la naturaleza de manera conceptual, su práctica artística se centra en el caminar y en la experimentación a través de sus caminatas. A partir de este proceso creativo, sus trabajos adquieren diversos formatos como: dibujo, fotografía / texto, esquemas escultóricos e intervenciones sobre la pared.

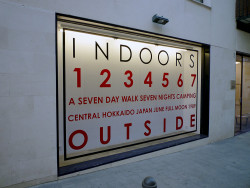

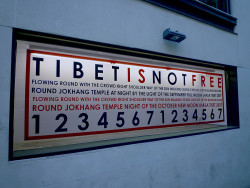

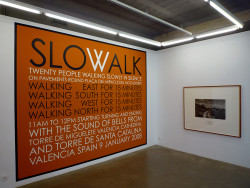

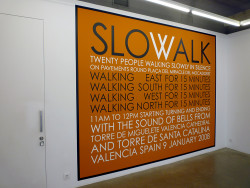

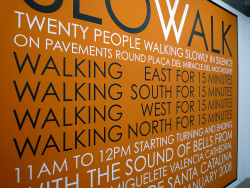

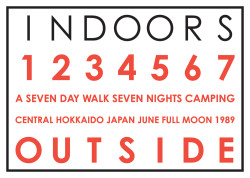

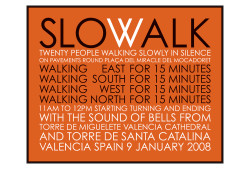

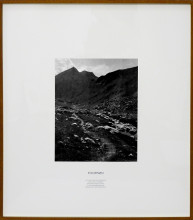

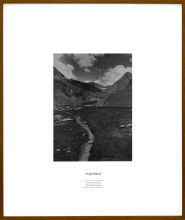

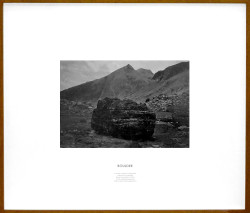

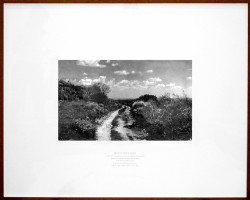

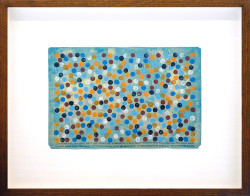

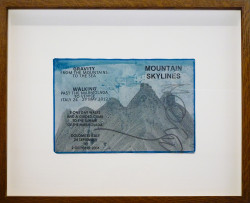

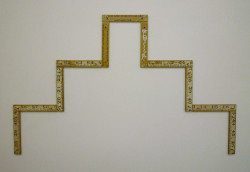

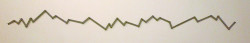

En esta exposición individual, se muestran tres intervenciones creadas especialmente para los diferentes espacios de la galería. En la primera sala se presenta una pieza realizada sobre la pared, Slowalk, 2008 (vinilo / pintura) basada en la caminata colectiva que realizó en Valencia. En el escaparate y la ventana exteriores de la galería se muestran otras dos piezas (vinilo sobre cristal), acerca de sus caminatas en Japón, 1989, titulada Indoors Outside, y el Tibet, 2007, titulada Tibet is not free. La exposición combina estas intervenciones junto con fotografías, de medio y gran formato, con texto, a partir de sus paseos en Pirineos, así como sus “walking works of wood”, y dibujos realizados a partir de sus paseos en Italia, 2004, 2012 y 2014, y en Suiza, 2007.

Para esta ocasión, Hamish Fulton vuelve a convocar a todo el público, que quiera asistir y vivir la experiencia, a realizar una caminata colectiva el sábado día 30 de mayo a las 11:30 en espaivisor. Desde la galería nos trasladaremos hasta un punto de la ciudad que el artista habrá elegido para realizar dicha acción.

Hamish Fulton essay Walk On catalogue, England 2013

WALKing is a seven letter word. The first seven steps. SOLSTICE FULL MOON. A SEVEN DAY WALK IN THE CAIRNGORM MOUNTAINS OF SCOTLAND. JUNE 1986. Simplicity. Walking transforms, walking is magic. Walking is good medicine. Walkabout. Today 2013, walking is more important than internet use. Wiki-walks. Opinion, is a seven letter word. Walking is ancient and contemporary. Consistently, walking is relation to everything. WINTER SOLSTICE FULL MOON. A CONTINUOUS WALK WITHOUT SLEEP ON THE PILGRIMS WAY FROM WINCHESTER TO CANTERBUTY. ENGLAND 21 22 23 DECEMBER 1991. (Pilgrimage routes - a loss of ego.) I am what I call a ‘walking artist’. Neither of these two words describes a conventional art medium (I’m not a sculptor or landscape photographer.) I’m not a conceptual artist. I transform ideas into experienced realities. I am an artist who walks, not a walker who makes art. Walking art is the bringing together of two entirely separate activities. WALKING IS AN ARTFORM IN ITS OWN RIGHT. WALKING IS THE CONSTANT, THE ART MEDIUM IS THE VARIABLE. With Richard Long, I made my first ‘artwalk’ (a seven letter word) as a student at St Martins in London on 2nd February 1967. But it would take me a further six years to gradually establish through trial and error a working practice. (Walks are constructed with self-imposed rules). 16 October 1973 after completing one coast to coast walk of just over a thousand miles from northeast Scotland to southwest England, age 27 I made the commitment: TO MAKE 100% ART RESULTING FROM THE EXPERIENCE OF INDIVIDUAL WALKS. Creativity. I believe in diversity (debate and discussion, we agree to disagree.) A diversity of walk categories, a diversity of artmaking, a diversity of artists. Most importantly, a diversity of lifeforms, GRASSES INSECTS. Commodities? The Rights os Nature. (The Oceans.) Let the art speak for itself? No so far. 1970’s art historians assumed my walking art into their chosen subjects, namely - landscape painting from the past and, outdoor sculpture in the present. No research into walking. L.A. Confidentiel: I was never influenced by the Romantics and I want no association with landArt (a seven letter word.) The collision between U.S. ‘leave-no-trace’? For the record, the starting date of my attitude was 1959 when I read about the life of Wooden Leg. a Northern Cheyenne who fought Custer. (25 June 1876.) History? Whose history? Justice? Justice for who? The rights of indigenous peoples. Ten years later, 13 September 1969 I walked - with Nancy Wilson, carrying that same book round the Little Bighorn battlefield. (Celebrity? There are no photographs of Crazy Horse.) By about 1977, I needed to ‘escape’ from landscape art (gardening and the English class system) I attended lectures by world-class mountaineers such as Doug Scott and emerged myself in expedition literature. I became an ‘armchair mountaineer’. GRAVITY. I am not a mountaineer or climber. I’m not scientific, not an engineer. As a walker, I find mountaineering inspirational. To quote the contemporary U.S. alpinist Steve House, ‘My ice axe may be your paintbrush’. I make walks in cities. INDOORS, is a seven letter word. I believe in solitary walks OUTSIDE combined with ‘wild’ camping. Tent life, close to the ground, closer to nature. Grasses, insects. I can keep walking all day bur I’m not a fast walker. Slowalk, is a seven letter word. At Tate Modern (30 April 2011) I made an indoor public communal walk titled, slowalk in support of Ai Weiwei. Protected by The Rule of Law? H.A.T. High altitude trekking. During the 49th day of the expedition we stood still on the summit of mount Everest, Chomolungma. Bardo. This experience was made possible for me only because I was guided by Sherpas. By Ang Dorje Sherpa of Pangboche. High and low, near and far. far away and long ago. A good question is, how far could you walk?. To date, my longest walk covered a distance of 2838 kilometres (carrying all my own luggage), coast to coast from Spain to the Netherlands. WALKING INTO THE DISTANCE BEYOND IMAGINATION. It is important to state that this not very long walk was ‘easy’. A very much harder, ‘gnarly’ walk might be a mere fraction of this length. From mountaineers I learnt the importance of route and style. After several years of failed attempts, I finally succeeded in: COUNTING 49 BAREFOOT PACES ON PLANET EARTH DURING EACH NIGHT OF THE TWELVE FULL MOONS FOR 2010. My hidden carbon footprint. Just one consequence of persistently ignoring nature is, global warming. Who cares about dates? Numbers is a seven letter word. Ursa Major. Quipu. Clock time, lifespan, death. Spring, summer, autumn, winter, Earth. The migration of whales, the migration of butterflies. (Lunar calendar.) No thing, is a seven letter word. Every thing is made of something. A mountain is not made of stone, it is stone. AN OBJECT CANNOT COMPETE WITH AN EXPERIENCE. Since 1973 every piece of art I have materialized (things) contains a walk text. I do not provide the relief of wordless art. (I don’t also make abstract art.) THERE ARE NO WORDS IN NATURE. The physical weight of (spoken) words. Talk the walk, THE WALK IS THE ART. SMALL ART BIG EXPERIENCE. Walking transforms, walking is magic. Tibetan Kora. Tibetan nuns. The last seven steps. Up to this time of writing, 99 Tibetans have self-immolated. History? Whose history?

The road to Utopia

In 1969 the artist Hamish Fulton followed in the footsteps of Sitting Bull, in a walk over the Little Big Horn battlefield in Montana. This is the hard, empty ground where the Sioux achieved their most celebrated victory over the US government in 1876, when George Custer and his 7th Cavalry attacked a teepee village only to be cut off in a ravine and wiped out. Fulton's walk over this resonant terrain was... what? A homage, an exploration, a re-enactment, a wilderness holiday? Or a work of art?

Now Fulton has an exhibition at Tate Britain that documents the hikes, climbs, rambles and road walks he has been undertak ing ever since, crossing vast tracts of the planet, traversing some of the remotest places on earth, leaving not a trace to mark his being there, bringing back not a thing.

When he visited the territories of the Plains Indians, Fulton was at the beginning of a long march. Born in 1946 in London, he was one of the generation of students at St Martin's School of Art who invented a distinctively British - romantic, solitary, whimsical, cussed - conceptual art at the end of the 1960s. Fulton was at St Martin's with Richard Long, and the two of them felt that walking across a place was an act so meaningful, distinct, conscious, that it deserved to be thought of as art.

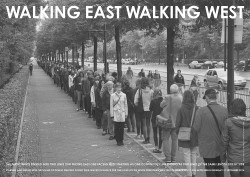

One of the first walks Fulton and Long engaged in was not in the wilderness, but the middle of London. They and a bunch of friends staggered from the corner of Greek Street and Old Compton Street round the corner to St Martin's, on Charing Cross Road. They weren't the first students to stumble through Soho, but they were all roped together, walking as a single body. It took ages.

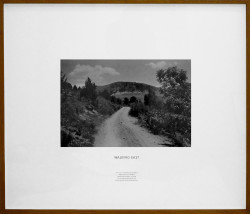

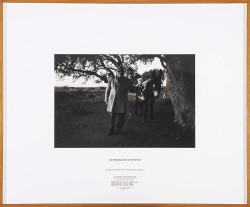

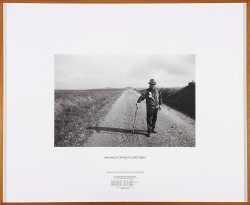

Walking Journey is an arresting, tantalising show. In an act of foolhardy generosity, Tate Britain has given over a vast exhibition space to an artist who has nothing to show except some framed photographs with reticent texts, cases of cards and artist's books and wall paintings using commonplace words against unexceptional colours. And just in case you start savouring the classic beauty of his photographs of Himalayan boulders and American riverbeds, or appreciating the graphic ingenuity of his wall paintings, be advised that none of this is the core of his art, which is the walking - what you see is evidence that his art happened, that he walked from point A to point B.

What makes the repetitiveness, dryness, silence of this exhibition so triumphant is not some chic pleasure in nothingness but something more difficult to accept and impossible to let go. Fulton's art is a goad. Its purpose, seen in a gallery in one of the densest cities on earth, is to make you realise that this is not where it's at. There are other places. There is another pulse - that of the wilderness, that of nature. There are, still, ways of inhabiting the earth that make you feel small, transient, mortal. And this recognition is political.

The problem with attempts to make political art today is the absence of utopia. Utopianism and the possibility of total, revolutionary change were part and parcel of modern life from the socialist experiments of Robert Owen in the early 19th century to the end of communism in Europe in the late 1980s. Now this sense of other possibilities is more etiolated than ever. Fulton however, in his endless walk, is an exponent of a visionary politics that has survived since the very beginnings of industrialisation. He is a romantic anti-capitalist in the same way the young William Wordsworth was when, penniless, he walked across Salisbury Plain in 1793 feeling like an exile in conservative Britain.

Fulton would be a romantic in an almost quaint way, if his art were not so hard. He believes in romantic things: in the purity and specialness of nature, in the idea of the wilderness, the shrinking yet still just discoverable margin of uncolonised, uncivilised earth. Like Rousseau and the idealists of the age of the French Revolution, he worships peoples at one with wildness.

The political provocation of Fulton's art - which is inseparable from its beauty - lies, however, not in transporting us into the heart of landscape, as JMW Turner did when he brought back stormy painted documents of his own travels, but making us longingly aware of the absence of landscape.

Nor does Fulton give us anything to compensate for the fact that we are stuck here in the city while he is in the Himalayas. His photograph-and-text pieces are the ultimate holiday postcard. Just as a postcard from someone else's exotic holiday can only ever make the recipient envious, Fulton's photographs tease and frustrate. A road vanishing in the desert, a boulder encountered in the mountains, a milestone. A track through leafy England has the pastoral seductiveness of Constable's east Sussex dirt track in his 1826 painting The Cornfield. Yet where Constable's painting, which hangs in the National Gallery, brings the country into Trafalgar Square, giving you a nostril full of cow dung, Fulton insists that his picture is no more than an inadequate souvenir of the walk to which it alludes. Underneath the photograph is one of the laconic texts that point to his experiences: "A nine and a half day coast to coast walk from Norfolk to Dorset travelling on country lanes and paths. The Peddars Way - The Icknield Way - The Ridgeway. England July 1997.”

That's all we get: a document banal in its lack of emphasis, were it not for the grave, quiet loveliness of tone. All the things he must have seen and heard in a walk across England from coast to coast are for us to imagine. We are in the position of Coleridge in his poem This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison, when he imagines the delights of a party of friends who have gone for a walk he cannot join because of an injury: "Well, they are gone, and here I must remain/This lime-tree bower my prison! I have lost/Beauties and feelings, such as would have been/Most sweet remembrance…"

Like Coleridge, we didn't have that experience, see those beauties, hear that bird sing on the Ridge way that morning, after the rain; and our prison is not even a lime-tree bower but a museum.

Fulton's purpose is not to satisfy us with an image but to point to a lack in our lives - it is like advertising. He wants to advertise a form of life that he believes to be good. Fulton's pictures and graphics tell you again and again that it would be better, freer, more beautiful a long way from here, in another place and time. He has made the advertising analogy explicit in big, billboard-sized works. They are no more substitutes for natural landscapes than his earlier photos - on the contrary, the spur is more powerful, insistent, more satirically desperate. He mimics the graphics and promise of posters that use landscape to sell things. Warm Dead Bird, Spain 1990, has the look of a classy ad, and yet it points to an experience we did not and cannot have, that is gone like the dead bird, and that is threatened by the pace and violence of the modern world. "Walking against the oncoming traffic", the view of a road in southern Spain is marked.

The fact of another place is all Fulton wants to tell us about - not show, but tell; not give, but promise, in that we can go his way, follow his road. Text paintings tell us this with superb economy, big letters arranged in visual analogy to what he saw. Strangely these works, without even photographs to help us picture the scene, are the closest to the pleasures of traditional landscape art. The layering of the word "clouds" over "stones", for example, says enough about a walk in Wyoming to make you picture a desolate glory.

Fulton has spent more than 30 years honing an art that is defiantly deictic, its purpose to point to something. In an early photograph, he indicates a landscape with a stick, and he has never tried to do more than this. His art is a signpost, directing us to the last wilderness regions, to the freedoms of the pastoral. By always pointing to other places, other times, he keeps utopia alive; his art is radical because it is joyous, pleasurable. The pleasure is not given us here to enjoy for a moment before we get on with our busy lives, but as a possible reward if we change our lives. What he shows us is otherwise just a souvenir. A wall painting tells us that in 2000 he climbed to the summit plateau of Cho Oyu (8,175 metres) in the Himalayas without oxygen. Only a simple graphic of a sun rising out of a crescent hints at the splendour he saw.

Walking Journey is at Tate Britain, London SW1 (020-7887 8008), until June 4.

Publication