space #1 - gallery

space #1 - gallery

CONOCIENDO A HAMISH

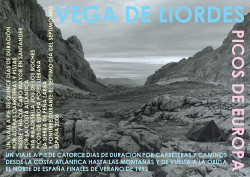

El día veinticinco de junio de 2006 Hamish Fulton desayunó muy temprano y partió hacia Cabo Mayor, Santander, para comenzar su andadura por tierras cántabras. Cuando me desperté él ya no estaba, y era consciente de que, a no ser por algún contratiempo, no sabría nada de él hasta que terminara su recorrido. Quince días después me llamó desde el aeropuerto de Santander para comunicarme el final de su viaje.

A lo largo de su extensa trayectoria, Hamish Fulton (Londres, 1946) ha demostrado ser un artista comprometido y fiel a su labor artística. Durante este tiempo han sido innumerables los textos escritos sobre su proceso de trabajo, en que la experiencia personal de sus viajes, a pie, por todo el mundo han dado como resultado una producción artística en la que naturaleza, fotografía y texto se funden indivisiblemente. Muchos somos los que conocemos, en mayor o menor detalle, lo que se ha escrito sobre su obra; sin embargo, para esta ocasión quizás sería interesante averiguar cómo es el Hamish Fulton persona.

Por tanto, este texto breve no intenta ser un análisis exhaustivo de su trabajo sino una somera descripción de lo que ha significado para mí colaborar con él. Desde que la Sociedad Gestora Año Lebaniego me planteó la posibilidad de invitar a Hamish Fulton a realizar un proyecto específico en Cantabria con motivo de la conmemoración del Año Jubilar Lebaniego, he profundizado en su trayectoria artística, pero al mismo tiempo, inevitablemente, he descubierto al Fulton más humano. He investigado sobre su perfil más público, es decir su producción artística, la más conocida por todos, pero también he tenido el placer de vislumbrar su parte más íntima, aquella que no se descubre hasta permanecer con él varios días, y puedo decir que las dos facetas son inseparables.

En un intento por describir su personalidad diría que se trata de una persona vital, educada y divertida. Hamish Fulton posee un carácter afable que hace que te sientas a gusto junto a él. Las sucesivas llamadas telefónicas y las numerosas charlas mantenidas durante los días anteriores a su viaje por tierras cántabras me demostraron su gran adaptabilidad y comprensión a la hora de salvar cualquier obstáculo que dificultara la realización del proyecto. Durante los días previos a su partida recorrimos diversas librerías y centros de información y turismo de Santander, buscando y comparando mapas y guías de la comunidad cántabra. Era necesario estudiar la máxima información sobre la región para ajustar el itinerario al máximo. No obstante, durante esos días también hubo tiempo para descubrir a un Fulton interesado por cuestiones sociales y políticas, tanto de carácter nacional como internacional. En esos momentos también afloró ese humor crítico, agudo e irónico que caracteriza a tantos británicos. En definitiva, conocí a una persona cercana y activa, y en ningún momento surgieron diferencias generacionales.

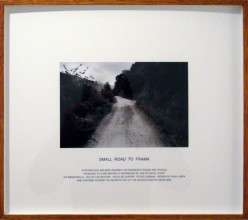

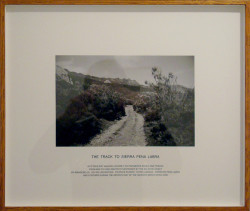

Por otro lado, y en un intento por describir su labor artística, diría que es un profesional en todos los sentidos, como demuestra la impecable producción de sus obras, en las que fotografía, texto y marco conviven de tal manera que ninguno de ellos destaca por encima de otro. Si nos referimos a su procedimiento de trabajo, a su lado más aventurero, todo se encuentra bajo un exhaustivo control, intentando ahorrar al máximo esfuerzos y riesgos innecesarios. La ruta debe estar bien definida, el mapa tiene que ser comprensible y a escala visible, la tienda y el saco deben ser de calidad y poderse plegar infinitamente, el calzado tiene que estar acorde con el itinerario marcado, la comida tiene que ser deshidratada y no presentar ningún tipo de envoltorio que ocupe espacio, y sobre todo, el artista tiene que disponer de un buen libro y un bloc de notas. Así, a la hora de partir dejó en el hotel todas las guías, los mapas y los folletos consultados, seleccionando un único ejemplar de cada uno, además de las anotaciones escritas en su bloc personal, un sinfín de detalles para hacer el viaje (su principal objetivo) lo más cómodo posible. El conocimiento acumulado desde principios de los años setenta lo han convertido en un experto en el medio natural, y han dado lugar a innumerables experiencias personales. De manera similar, la exhaustiva organización y la escasez de recursos caracterizan los medios empleados para realizar sus instantáneas: únicamente una cámara de pequeño formato.

Para referirme a su vertiente más estética diría que se trata de un artista indeterminado, no clasificable dentro de una única corriente. Sus dibujos, esquemas escultóricos, murales sobre la pared y la utilización de la imagen fotográfica, acompañada de textos descriptivos y fechas del tiempo transcurrido en sus viajes, han hecho que habitualmente se le clasifique dentro del land art, a pesar de que posiblemente no esté demasiado de acuerdo con esta clasificación e ironice al respecto, como demostró al publicar la frase THIS IS NOT LAND ART (Esto no es land art) en la tarjeta de invitación a una de sus exposiciones. Si bien es cierto que su obra nos acerca a la naturaleza de manera conceptual, por medio de imágenes que documentan puntualmente el paisaje que va atravesando, junto con textos descriptivos del tiempo transcurrido, quizás con este tipo de documentación –fotografía en blanco y negro, más el texto sobre la localización y el tiempo exactos– evidencie la imposibilidad del espectador de experimentar la naturaleza tal y como la ha vivido el artista. De ahí que, a pesar del intento de documentar y describir la experiencia, el espectador no pueda evitar sentir envidia por no haber estado allí, recorriendo y caminando. Quizás encarnar parte de la historia del arte de nuestros días sea el precio que deba pagar Fulton por el privilegio de codearse así con la naturaleza.

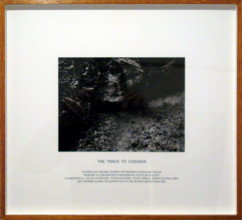

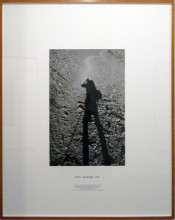

Es innegable que los trabajos que Hamish Fulton ha realizado en Cantabria sirven para que conozcamos la riqueza de su geografía. Las imágenes de espacios abiertos –valles, montañas, ríos, caminos o carreteras– son las que mejor describen su recorrido. Sin embargo, me gustaría destacar otros tres tipos de imágenes que, sin ser las más representativas de esta andanza, sin duda son testimonio fiel de la estrecha correspondencia entre la persona y el artista: me refiero a las imágenes en las que aparece el propio artista a modo de autorretrato. En primer lugar, quisiera mencionar las fotografías en las que su presencia queda patente de forma metafórica a través de su mochila, su tienda de campaña, su sombra proyectada en el suelo o incluso la silueta de un peatón convertido en diablo por medio de un graffiti; todas ellas me sugieren la imagen de su propia alma, especialmente la de su mochila, que parece convertirse en un cónyuge fiel. En segundo lugar, me refiero a esas fotografías en las que vemos una única roca en el centro de la imagen, como si se tratase del encuentro casual con otro caminante, con quien se conversa brevemente para compartir la experiencia. Finalmente, en tercer lugar, aunque ya no se trate de fotografías sino de páginas diseñadas por el artista con motivo de esta publicación, quisiera citar el mapa marcado con el itinerario y el collage configurado a partir de las diferentes etiquetas de agua embotellada que compró a lo largo del recorrido. Estas dos imágenes parecen representar una parte vital de su viaje y de sí mismo, una manera de coleccionar recuerdos azarosos y ligeros con evocaciones a la naturaleza. A diferencia de los paisajes, en estos tres ejemplos intuimos la presencia humana y vemos reflejada la identificación entre artista y persona. Quizás podamos considerarlos una representación de su álter ego, o la respuesta a la necesidad primitiva e instintiva del ser humano de relacionarse con otros. En estas obras Hamish tal vez nos esté mostrando, inconscientemente, la necesidad de sentirse persona antes que artista. Como él mismo afirma, «caminar no es una recreación o un estudio de la naturaleza (ni hacer poesía ni detenerse para realizar esculturas al aire libre o tomar fotografías). Caminar es un intento por sentirme física y mentalmente superado –con el deseo de flotar a través del ritmo que se crea caminando– para experimentar un estado de euforia temporal, una íntima relación de mi mente con el mundo natural exterior».

Por último, quisiera agradecer a Hamish Fulton el magnífico trabajo realizado, recopilado en esta publicación, así como haberme convertido en su ayudante durante esta breve pero intensa experiencia, la cual me ha brindado la posibilidad de conocerle mejor. También quisiera agradecer a la Sociedad del Año Lebaniego y al Gobierno de Cantabria por incluir este proyecto en su programación. Finalmente, quisiera dar las gracias a todas aquellas personas que han participado de alguna manera en el proyecto, que espero que contribuya a difundir la comarca de Liébana y a Cantabria en general.

Mira BernabeuThe road to Utopia

In 1969 the artist Hamish Fulton followed in the footsteps of Sitting Bull, in a walk over the Little Big Horn battlefield in Montana. This is the hard, empty ground where the Sioux achieved their most celebrated victory over the US government in 1876, when George Custer and his 7th Cavalry attacked a teepee village only to be cut off in a ravine and wiped out. Fulton's walk over this resonant terrain was... what? A homage, an exploration, a re-enactment, a wilderness holiday? Or a work of art?

Now Fulton has an exhibition at Tate Britain that documents the hikes, climbs, rambles and road walks he has been undertak ing ever since, crossing vast tracts of the planet, traversing some of the remotest places on earth, leaving not a trace to mark his being there, bringing back not a thing.

When he visited the territories of the Plains Indians, Fulton was at the beginning of a long march. Born in 1946 in London, he was one of the generation of students at St Martin's School of Art who invented a distinctively British - romantic, solitary, whimsical, cussed - conceptual art at the end of the 1960s. Fulton was at St Martin's with Richard Long, and the two of them felt that walking across a place was an act so meaningful, distinct, conscious, that it deserved to be thought of as art.

One of the first walks Fulton and Long engaged in was not in the wilderness, but the middle of London. They and a bunch of friends staggered from the corner of Greek Street and Old Compton Street round the corner to St Martin's, on Charing Cross Road. They weren't the first students to stumble through Soho, but they were all roped together, walking as a single body. It took ages.

Walking Journey is an arresting, tantalising show. In an act of foolhardy generosity, Tate Britain has given over a vast exhibition space to an artist who has nothing to show except some framed photographs with reticent texts, cases of cards and artist's books and wall paintings using commonplace words against unexceptional colours. And just in case you start savouring the classic beauty of his photographs of Himalayan boulders and American riverbeds, or appreciating the graphic ingenuity of his wall paintings, be advised that none of this is the core of his art, which is the walking - what you see is evidence that his art happened, that he walked from point A to point B.

What makes the repetitiveness, dryness, silence of this exhibition so triumphant is not some chic pleasure in nothingness but something more difficult to accept and impossible to let go. Fulton's art is a goad. Its purpose, seen in a gallery in one of the densest cities on earth, is to make you realise that this is not where it's at. There are other places. There is another pulse - that of the wilderness, that of nature. There are, still, ways of inhabiting the earth that make you feel small, transient, mortal. And this recognition is political.

The problem with attempts to make political art today is the absence of utopia. Utopianism and the possibility of total, revolutionary change were part and parcel of modern life from the socialist experiments of Robert Owen in the early 19th century to the end of communism in Europe in the late 1980s. Now this sense of other possibilities is more etiolated than ever. Fulton however, in his endless walk, is an exponent of a visionary politics that has survived since the very beginnings of industrialisation. He is a romantic anti-capitalist in the same way the young William Wordsworth was when, penniless, he walked across Salisbury Plain in 1793 feeling like an exile in conservative Britain.

Fulton would be a romantic in an almost quaint way, if his art were not so hard. He believes in romantic things: in the purity and specialness of nature, in the idea of the wilderness, the shrinking yet still just discoverable margin of uncolonised, uncivilised earth. Like Rousseau and the idealists of the age of the French Revolution, he worships peoples at one with wildness.

The political provocation of Fulton's art - which is inseparable from its beauty - lies, however, not in transporting us into the heart of landscape, as JMW Turner did when he brought back stormy painted documents of his own travels, but making us longingly aware of the absence of landscape.

Nor does Fulton give us anything to compensate for the fact that we are stuck here in the city while he is in the Himalayas. His photograph-and-text pieces are the ultimate holiday postcard. Just as a postcard from someone else's exotic holiday can only ever make the recipient envious, Fulton's photographs tease and frustrate. A road vanishing in the desert, a boulder encountered in the mountains, a milestone. A track through leafy England has the pastoral seductiveness of Constable's east Sussex dirt track in his 1826 painting The Cornfield. Yet where Constable's painting, which hangs in the National Gallery, brings the country into Trafalgar Square, giving you a nostril full of cow dung, Fulton insists that his picture is no more than an inadequate souvenir of the walk to which it alludes. Underneath the photograph is one of the laconic texts that point to his experiences: "A nine and a half day coast to coast walk from Norfolk to Dorset travelling on country lanes and paths. The Peddars Way - The Icknield Way - The Ridgeway. England July 1997."

That's all we get: a document banal in its lack of emphasis, were it not for the grave, quiet loveliness of tone. All the things he must have seen and heard in a walk across England from coast to coast are for us to imagine. We are in the position of Coleridge in his poem This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison, when he imagines the delights of a party of friends who have gone for a walk he cannot join because of an injury: "Well, they are gone, and here I must remain/This lime-tree bower my prison! I have lost/Beauties and feelings, such as would have been/Most sweet remembrance..."

Like Coleridge, we didn't have that experience, see those beauties, hear that bird sing on the Ridge way that morning, after the rain; and our prison is not even a lime-tree bower but a museum.

Fulton's purpose is not to satisfy us with an image but to point to a lack in our lives - it is like advertising. He wants to advertise a form of life that he believes to be good. Fulton's pictures and graphics tell you again and again that it would be better, freer, more beautiful a long way from here, in another place and time. He has made the advertising analogy explicit in big, billboard-sized works. They are no more substitutes for natural landscapes than his earlier photos - on the contrary, the spur is more powerful, insistent, more satirically desperate. He mimics the graphics and promise of posters that use landscape to sell things. Warm Dead Bird, Spain 1990, has the look of a classy ad, and yet it points to an experience we did not and cannot have, that is gone like the dead bird, and that is threatened by the pace and violence of the modern world. "Walking against the oncoming traffic", the view of a road in southern Spain is marked.

The fact of another place is all Fulton wants to tell us about - not show, but tell; not give, but promise, in that we can go his way, follow his road. Text paintings tell us this with superb economy, big letters arranged in visual analogy to what he saw. Strangely these works, without even photographs to help us picture the scene, are the closest to the pleasures of traditional landscape art. The layering of the word "clouds" over "stones", for example, says enough about a walk in Wyoming to make you picture a desolate glory.

Fulton has spent more than 30 years honing an art that is defiantly deictic, its purpose to point to something. In an early photograph, he indicates a landscape with a stick, and he has never tried to do more than this. His art is a signpost, directing us to the last wilderness regions, to the freedoms of the pastoral. By always pointing to other places, other times, he keeps utopia alive; his art is radical because it is joyous, pleasurable. The pleasure is not given us here to enjoy for a moment before we get on with our busy lives, but as a possible reward if we change our lives. What he shows us is otherwise just a souvenir. A wall painting tells us that in 2000 he climbed to the summit plateau of Cho Oyu (8,175 metres) in the Himalayas without oxygen. Only a simple graphic of a sun rising out of a crescent hints at the splendour he saw.

Walking Journey is at Tate Britain, London SW1 (020-7887 8008), until June 4.

Publication